Judith and Holofernes

- Date of Creation:

- 1460

- Height (cm):

- 236.00

- Medium:

- Other

- Subject:

- Figure

- Created By:

- Current Location:

- Florence, Italy

- Judith and Holofernes Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Sculptures

- Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Judith and Holofernes Story / Theme

The story behind Judith and Holofernes comes from the Bible - the deuterocanonical book of Judith. The Bible tells us that the King of Nineveh, Nebuchadnezzar, sent his general, Holofernes, to subdue his enemies, the Jews. The Jews are besieged in Bethulia and rapidly lose all hope of victory. Famine further undermines their courage and they begin considering surrender.

Judith, whose name means "lady Jew" or "Jewish woman", was a strikingly beautiful widow. She overhears plans for surrender and decides to "deliver the city". She creeps into the Assyrian camp, seduces Holofernes with her captivating beauty, waits until he is thoroughly drunk, and cuts off his head.

She returns to her people victorious, holding up the severed head as a trophy. The Jews regain their courage, raid the Assyrian camp and drive the enemy away.

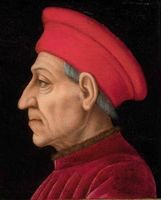

Judith and Holofernes was commissioned by Cosimo de Medici to stand beside fellow tyrant-slayer David (another of Dontaello's works) in the garden of the Medici palace. It appears that independence and freedom from oppression were favorite artistic themes among the Medicis, one of the wealthiest and most famous families in all of Tuscany and the chief defenders of Florentine liberty.

It is said that the statues' pedestal was once inscribed with; "Kingdoms fall through luxury, cities rise through virtues. Behold the neck of pride severed by the hand of humility".

Another inscription is said to have read; "The salvation of the state. Piero de Medici son of Cosimo dedicated this statue of a woman both to liberty and to fortitude, whereby the citizens with unvanquished and constant heart might return to the republic. "

However, the only surviving inscription is Donatello's signature, making Judith and Holofernes Donatello's only signed work.

Judith and Holofernes Inspirations

The statue of Judith and Holofernes was commissioned by Cosimo de Medici who, as leader of Florence's foremost family had a vested interest in presenting at all times an appearance of unity and freedom. Artwork was a particularly easy way to do that.

Cosimo's lifelong friendship with Donatello meant that the artist was always at the patron's beck and call; throughout his life Donatello produced numerous works for Cosimo and the Medici family palace. The struggle with and victory over tyranny and oppression were common themes in several of the works that Donatello completed for the Medici family. Judith and Holofernes is one such work.

It depicts Judith, an admirably courageous Jewish woman, cutting off the head of a foreign general who had been ordered to conquer the Jews. She was only a common, simple widow woman, but she defeated a powerful general.

This was perhaps meant to be metaphorical for the people of Florence: no matter how great or fearsome the enemy, even the smallest and weakest member of the resistance can make a difference. Judith herself is still considered an immortal symbol of peace, liberty, virtue, and victory over the strong by the weak.

Judith and Holofernes Analysis

Tone elicited:

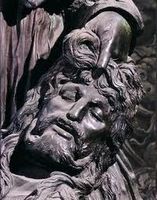

The overwhelming tone of the statue is one of strength, fearlessness and power. Judith stands triumphant over the slain Holofernes, a sword in her right hand raised over her shoulder as if about to strike once more.

The expression on her face is cold and defiant. The crumpled body of Holofernes lies at her feet; she holds his disembodied head by the hair and looks out victorious into the world.

Method:

It is believed that Judith and Holofernes was originally gilded (coated with gold); thus, its original shine, combined with the statue's emotional power, was probably stunning.

The bronze for the statue was cast in eleven parts to make the gilding easier. The sculpture was crafted in the round and has four distinct faces, providing the viewer with 360 degrees of intensely inspiring sculpture.

Attention to detail:

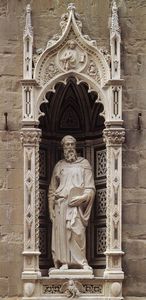

As with virtually all of his other works, Donatello focused on naturalism in Judith and Holofernes. The base of the sculpture, for example, is cushion-like and reminiscent of a similar device used in Donatello's St. Mark (in the Orsanmichele).

Judith's clothes are realistically mussed; there is a slightly wild look about her and her clothes fall naturally in folds along her raised arm. The body of Holofernes has been ingeniously crafted to perfectly resemble the ragdoll-like nature of the recently dead: the arm dangles unnaturally and the mouth is agape.

Two inscriptions (no longer visible) spoke wisely of the perils of pride and the courage and strength of humility, along with touting the Medici family as the defenders and saviors of Florence.

Judith and Holofernes Critical Reception

There is no information regarding how the statue of Judith and Holofernes was initially received. Presumably the Medici family was pleased with it or it would not have occupied such a position of honor in the Medici Palace garden. Over the years it would eventually be moved to a similar position of honor in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

Donatello is unique among most Renaissance artists for the massively wide appeal of his work. His sculptures were popular with clergy, art patrons and laypeople alike. His sculptures are almost exclusively focused on religious figures but were reinterpreted to incorporate Donatello's own style and a new understanding of the figures as individuals.

All of Donatello's sculptures reflect his fascination with individualism and naturalism and all appear to have been praised for doing so.

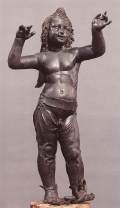

Judith and Holofernes Related Sculptures

Judith and Holofernes Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

Donatello's Judith and Holofernes was commissioned by Cosimo de Medici of the famous and wealthy Medici family. Upon its completion, it was placed in the garden of the Palazzo Medici alongside Donatello's bronze David.

In 1495, shortly after Donatello's death, Judith and Holofernes was placed on the Piazza della Signoria beside the main door of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. It was meant to commemorate the expulsion of Cosimo de Medici's son, Piero di Lorenzo de Medici, from Florence and Florence's new leadership under Girolamo Savonarola.

Its theme, then, was curiously turned against the family that it was meant to honor: Piero de Medici had become tyrannical; like the fabled Holofernes, his "head" was cut off by the Florentine people.

The statue was moved four more times following Piero's expulsion. A short while after its original move, it was transferred to the courtyard of the Palazzo Vecchio, and later into the Loggia dei Lanzi. In 1919, the statue was moved to the left side of the Palazzo Vecchio. It underwent restoration during the twentieth century, during which time it was briefly replaced by a bronze replica. Shortly after, it was moved to a permanent home in the Sala dei Gigli inside the Palazzo Vecchio.

Judith and Holofernes Artist

Donatello was a Florentine artist who worked and lived during the Early Renaissance. The son of a wool-carder, he was apprenticed early on to a goldsmith and a little later to Renaissance master Lorenzo Ghiberti.

Donatello struck out on his own in his late teens and met with instant success and acclaim. He worked alongside Brunelleschi for many years and together the two of them paved the way for the High Renaissance and the evolution of Western art as it is known today.

Donatello was known primarily for his fascination with individualism and naturalism, two crucial tenets of the Early Renaissance. He was obsessed with giving his subjects as human and as natural a look as possible, concentrating on giving them just the right posture, expression and gesture, as seen in Judith and Holofernes. Few, if any, will dispute that he reached his goal admirably; he produced some of the most important sculpture of the Renaissance and indeed in all of Western art.

Donatello was not a religious man but he was extraordinarily popular with the church for his vivid and deeply moving renderings of many religious figures. His preoccupation with emotion is probably responsible for the affecting quality of his work.

The artist spent considerable time in both Rome and Padua, where his fame and reputation continued to grow. While away from Florence, he sculpted the famous equestrian statue, Gattamelata, which broke the mold and would inspire artists for decades to come. Thus, Donatello was an immensely influential and vital part of the Renaissance.

Judith and Holofernes Art Period

The Early Renaissance was a time of slow but steady growth and experimentation. The art world was gradually moving beyond the rigidity and unimaginative Gothic movement and artists were beginning to experiment more with tone, theme and the overall appearance of their subjects.

For the first time, traditional interpretations of revered religious icons were acceptable: it was no longer strictly necessary to bathe all saints in holy light; now, they could be portrayed as the fallible humans that they were. They could experience joy, fear, anger, sorrow and everything in between.

The Early Renaissance was also characterized by a strong emphasis on individualism and naturalism. Artists began to place more importance on bringing out the details and minutiae of an individual.

Donatello and Brunelleschi are very often credited with moving the Early Renaissance into the High Renaissance - Donatello for sculpture, Brunelleschi for architecture. Both were visionaries in their respective fields. With the inspiration and insight their work provided, Western art was able to move forward to the time of Michelangelo, da Vinci, Raphael and other great artists.

Judith and Holofernes Bibliography

To find out more about Donatello please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Bennett, Bonnie A. & Wilkins, David G. Donatello. Moyer Bell Limited, 1985

• Brine, K. , Ciletti, E. , and Lähneman, H. The Sword of Judith. Judith Studies across the Disciplines. Open Book Publishers, 2010

• Janson, H. W. Sculpture of Donatello. Princeton University Press, 1979

• Lightbown, R. W. Donatello and Michelozzo: Artistic Partnership and Its Patrons in the Early Renaissance. Harvey Miller Publishers, 1980

• Lubbock, Jules. Storytelling in Christian Art from Giotto to Donatello. Yale University Press, 2006

• Migiel, M. and Schiesari, J. (eds. ) Refiguring Women: Perspectives on Gender and the Italian Renaissance. Cornell University Press, 1991

• Poeschke, Joachim. Donatello and His World: Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance. Harry N Abrams, 1993

• Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Donatello: Sculptor. Abbeville Press, 1993