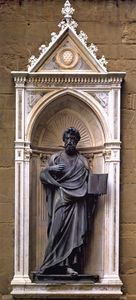

Mary Magdalen

- Date of Creation:

- circa 1457

- Height (cm):

- 188.00

- Medium:

- Wood

- Subject:

- Figure

- Created By:

- Current Location:

- Florence, Italy

Mary Magdalen Story / Theme

The story of Mary Magdalen herself is a sad one. She was a "woman of sin" (prostitute), famous for her beauty and long, flowing blond tresses, until she met Jesus and was delivered, according to the Bible, from "seven demons".

She became one of Jesus' most ardent followers, eventually becoming the leader of a group of female disciples who are often depicted at the base of the cross in portrayals of Jesus' crucifixion. Mary Magdalen is often considered a special, most-beloved disciple of Christ, who had a better understanding of his teachings and a stronger desire to live by them.

The Bible tells that she went at one point to live without food in a remote cave because she wished to survive solely on "heavenly nourishment". Whether this is true or not, Mary Magdalen's story has been a source of inspiration for many.

Despite biblical evidence to the contrary, there have been speculations that Mary Magdalen was Jesus' wife and even bore his children. This conflicts with several accounts that state that, following her witnessing of Jesus' resurrection on the third day after his crucifixion, she became a virgin once more.

Whatever the case, Mary Magdalen is an oft-honored saint in the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican and Lutheran churches. Donatello sculpted her as she is likely to have appeared in her later years: worn down by penitence and fasting, her once-striking beauty completely faded and her whole being focused on salvation.

Scholars disagree on the purpose of Donatello's Magdalen, but one prominent theory advocates that she was sculpted to provide hope and inspiration to the repentant prostitutes at the convent of Santa Maria Maddalena di Cestello. No records exist regarding the creation or original location, however.

Mary Magdalen Inspirations

Donatello's most likely source of information for the Magdalen came from his likely commissioners, the convent at Santa Maria di Cestello. The work was probably intended to provide comfort and inspiration to the repentant prostitutes housed at the convent.

Although this theory is sometimes disputed, no other theory has been successfully put forward. There are no surviving documents regarding the commission or creation of the Magdalen; its first appearance in the annals of history was in 1500, when a document indicates that the statue had been returned to the Baptistery in Florence.

In early Renaissance Florence, Mary Magdalen was especially popular with several mendicant religious orders such as the Franciscans and the Dominicans. They viewed her as an example to all women, with a devout and unyielding faith in God. These influential orders may also have influenced Donatello's creation of the Magdalen.

Whether Donatello created the Magdalen for the Baptistery or the convent is uncertain. What is known, however, is that the life of Saint Mary Magdalen has been a source of tremendous inspiration for tens of millions of rehabilitated women and men alike. She was and remains an oft-celebrated figure of the utmost piety and devotion to her faith in Jesus Christ.

Mary Magdalen Analysis

Composition:

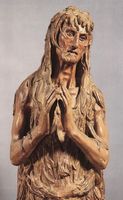

Donatello's Mary Magdalen is so strikingly, reverberatingly emotional that there is no shortage of scholarly comment on its composition. Donatello clearly meant to make a statement with this piece; her appearance is so arresting that it almost commands viewers to look at its obvious suffering.

The Magdalen stands nearly two meters tall - almost freakishly tall for either a man or a woman - and is composed entirely of wood. At first glance, the Magdalen appears to be shrouded completely in rags; however, upon closer inspection it is clear that she is represented as she was reputed to be in life - covered from head to toe by her famously long, blond locks.

Her hands are close together in front of her, the fingertips barely touching, in a gesture of piety and repentance. Her right knee is bent as if she is about to take a step, and the weight-bearing left leg seems to support this notion. She is appropriately positioned in front of a statue of Christ in the Duomo Museum, making it seem like she is attempting to walk toward him.

Attention to detail:

The appearance of the Magdalen's body is frequently a subject of contention. Many scholars described her as psychotic-looking and skeletal or "half-mad", perhaps from years spent fasting in a cave in an attempt to fully cleanse herself of sin.

However, a closer look reveals much more. Slender though she certainly is, the Magdalen is not necessarily weak and emaciated. She clearly possesses a unique strength of mind and body. Her arms are surprisingly sinewy and even faintly masculine. Her hair, disheveled and probably unwashed, hangs like a blanket around her shriveled body.

Though her face evokes feelings of revulsion in some, there can be no doubt that her expression is one of fierce devotion and determination.

Striking features:

Other features bear mention: her decidedly elongated torso, her parted, parched lips, broken teeth, and seemingly unsteady stance. The Magdalen is a shocking, vibrant work of art that, consistent with Donatello's reputation, broke free of all conventions.

Mary Magdalen Critical Reception

During life:

Since there are no surviving documents related to the creation and "life" of Donatello's Mary Magdalen, it is difficult to say how the statue was received at the time of its completion. In all likelihood, however, the statue was appreciated for its emotional rawness and realism.

Although the Magdalen had in the past typically been portrayed as flawlessly beautiful with long, flowing blond tresses, Donatello chose to represent her as she likely was after decades of fasting, penitence and self-denial.

It is possible that the Magdalen caused a stir simply because she was not presented as a beautiful woman. The statue has been described as "repulsive, horrifying, terrible, emaciated", and many other unflattering names. However, such adjectives indicate the high level of emotion that the Magdalen had and continues to evoke in viewers.

Also, as the Magdalen was most likely created for a convent that housed repentant prostitutes, the strength and determination that the statue exudes was probably incredibly inspiring for the fallen women who saw it on a daily basis.

After death:

Following Donatello's death, the lack of information regarding the Mary Magdalen persisted. However, in the twentieth century there was renewed interest among the scholarly community in the statue.

Scholars are unified in their respect for the craftsmanship of the statue; no one has ever doubted Donatello's extraordinary skill. Where artists have been divided is regarding the proper interpretation of the Magdalen's appearance.

Some believe that she is meant to appear emaciated, weak and on the verge of insanity. Others, like Martha Levine Dunkelman, believe that the statue was meant to communicate a determined, almost superhuman strength and devotion. Thin though she certainly is, Dunkelman says, her clear-sightedness and piety are obvious.

Mary Magdalen Related Sculptures

Mary Magdalen Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

As there are no documents providing any information about the commission or creation of Donatello's Mary Magdalen, and scant details regarding the statue's existence, it is difficult to say where the statue has stood over the centuries.

Most scholars believe that the Magdalen was created for the convent at Santa Maria di Cestello, a religious house that provided a haven for fallen women (repentant prostitutes). The Magdalen was probably meant as a source of hope and inspiration for the women who were struggling to rebuild their lives.

The first mention of the statue's location was in 1500, when the Magdalen was said to have been in the Baptistery in Florence. A document from October 30, 1500 states that the statue "used to be in the Baptistery and was then removed and put in the workshop, ... and put back in the church".

Whether the Baptistery was the Magdalen's original location is a matter of some debate, but many scholars believe it was. It probably remained in the Baptistery until the terrible Florentine flood of 1966, when it was washed away.

Upon location and cleaning, to the delight of the art community, the statue's original polychrome and gilding was discovered. Afterwards, the Magdalen was placed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, where she remains today.

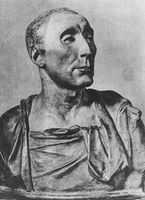

Mary Magdalen Artist

Donatello was one of the most talented and influential artists of the entire Renaissance. He was born in Florence, the son of a wool-carder, and spent his youth training for what would become a truly glorious career. He was first apprenticed to a goldsmith, then to the Italian master Lorenzo Ghiberti but struck out on his own aged 17.

Donatello followed contemporary Filippo Brunelleschi to Rome, where the two young men spent years excavating the ancient grounds and fine-tuning their respective crafts - sculpting for Donatello, architecture for Brunelleschi.

When Donatello returned to Florence, he did so an established and very highly-respected artist, having produced such works as the bronze David and received commissions from several prestigious patrons.

He was a favorite and lifelong friend of Cosimo de Medici, who petted and feted him throughout their friendship and kept him busy with commissions almost until his death.

Donatello was famous for his striking ability to merge the stylized ideals of classicism with the realistic, humanized techniques of the Renaissance in a way that seemed completely seamless and natural. He is today revered for urging the art world into the High Renaissance and left us with many priceless works.

Mary Magdalen Art Period

The Mary Magdalen is typically categorized as Early Renaissance art. At the time of its production in 1457, the art world was still crawling out of Gothicism at a snail's pace (that was slowly gaining speed); Giotto had urged it along somewhat with his revolutionary naturalism and humanism in the fourteenth century, but discernible change was still about half a century away.

While his contemporaries stuck mostly to Gothicism, with a few innovations, Donatello studied the classic works of Greece and Rome. Out of his studies and ruminations came Donatello's gap-bridging efforts between the classical world and the Renaissance.

During the Early Renaissance, Donatello was surrounded by many famous and talented artists, among them Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Masaccio, Jacopo della Quercia and Michelozzo. Along with their contemporaries, these artists gave birth to the High Renaissance and the genius of Michelangelo, da Vinci and many others.

Mary Magdalen Bibliography

To learn more about Donatello please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Bennett, Bonnie A. & Wilkins, David G. Donatello. Moyer Bell Limited, 1985

• Clement, Clara Erskine. A Handbook of Legendary and Mythological Art. 2010

• Janson, H. W. Sculpture of Donatello. Princeton University Press, 1979

• Jameson, Anna Brownell. Sacred and legendary art. Longmans & Green, 1874

• Lightbown, R. W. Donatello and Michelozzo: Artistic Partnership and Its Patrons in the Early Renaissance. Harvey Miller Publishers, 1980

• Lubbock, Jules. Storytelling in Christian Art from Giotto to Donatello. Yale University Press, 2006

• Poeschke, Joachim. Donatello and His World: Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance. Harry N Abrams, 1993

• Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Donatello: Sculptor. Abbeville Press, 1993