Donatello

- Full Name:

- Donato di Niccolo di Betto Bardi

- Date of Birth:

- circa 1386

- Date of Death:

- 12 Dec 1466

- Focus:

- Sculpture

- Mediums:

- Other

- Subjects:

- Figure

- Hometown:

- Florence, Italy

Introduction

Second only to Michelangelo in terms of skill and sheer greatness, Florentine sculptor Donatello left an indelible mark on the Renaissance and the future of art itself. Donatello shot to fame early on as an apprentice to Lorenzo Ghiberti and eventually became one of the most sought-after artists in Italy for his life-like, highly emotional sculptures.

Donatello first received training at a goldsmith's shop and then with Ghiberti. He launched a solo career during the first decade of the thirteenth century and met with success after success in his eighty years. During his lifetime, Donatello completed some of the most well-known sculptures in Western art including David, Mary Magdalen and the compelling Gattamaleta. He dedicated his life to serving the church and the Medici family and today his works can be found in prestigious art museums and galleries throughout Europe.

Donatello Biography

Scant information exists regarding Donatello's personal life; even his date of birth is disputed and the first recorded indication of his existence was not made until 1406.

Early years:

Donatello was born around 1386 to Florentine Woolcombers Guild member Nicolo di Betto Bardi. Christened Donato di Niccolo di Betto Bardi, his friends and family adopted the nickname by which he is known today - Donatello. His first educational setting was the shop of a goldsmith, where he presumably learned the craft and developed an interest in manipulating metals and other substances. He later worked for a short time in the studio of his mentor, Lorenzo Ghiberti.

In 1402 Ghiberti won a competition to design the North Baptistery gates, beating other notable artists Brunelleschi and Jacopo della Quercia (Donatello was too young to participate). Afterwards, when a brooding, disappointed Brunelleschi departed for Rome to study the remnants of classical art, Donatello tagged along and the two began a lifelong friendship and professional rivalry.

In Rome, the two young men gained a reputation as treasure seekers for their excavations in classic soil while they worked in various goldsmiths' shops to support themselves. The Roman years brought Donatello his understanding of ornamentation and classic forms, pivotal knowledge that would eventually change the face of fifteenth-century Italian art.

Both Donatello and Brunelleschi would become the leading artistic lights of the early Renaissance - Brunelleschi for architecture and Donatello for sculpture.

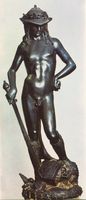

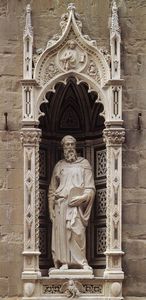

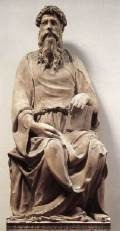

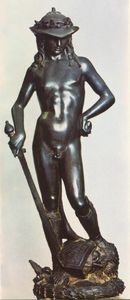

Donatello received his first recorded payment as an independent sculptor in 1406, though the work for which he was paid is unknown. He completed the world-famous David in 1408, followed by the Orsanmichele St. Mark in 1413 and St. John the Evangelist in 1415.

Donatello's imposing, larger-than-life figures cemented his reputation for innovation and extraordinary skill. He finished up his third decade with the mold-breaking St. George in 1417; that same year, he completed the miniature relief St. George and the Dragon.

Middle years:

Donatello's professional success continued unabated throughout his middle years, which were punctuated with such illustrious works as Feast of Herod, Annunciation and Singing Gallery. In 1425, Donatello began a partnership with architect and sculptor Michelozzo and together they journeyed to Rome in around 1429.

While in Rome, the two collaborated on the tomb of Pope John XXIII in the Baptistery in Florence and the tomb of Cardinal Brancacci in St. Angelo in Naples. Donatello's innovations in burial chambers would later influence many other Florentine tombs.

Advanced years:

The decade between 1443 and 1453 was spent in Padua, where Donatello completed one of his best-known and most admired works, the Gattamelata. Somewhat controversial at the time, the Gattamelata was an equestrian statue created in the image of Venetian condottiere Erasmo da Nami. Typically, equestrian statues of this kind were reserved for rulers and kings. The statue can still be seen today in the Piazza del Santo.

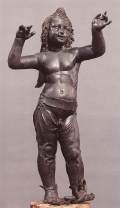

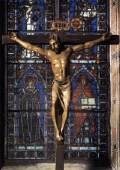

During his time in Padua, Donatello also completed the high altar of St. Antonio: four oversized reliefs narrating the life of St. Antonio, several smaller reliefs, and seven bronze life-sized sculptures (including the Madonna and Child and the Crucifixion). This accomplishment brought yet more acclaim for Donatello's revolutionary experimentation with illusions of and other ideas about space.

By 1455 Donatello had returned to Florence and completed the haggard-looking but renowned Mary Magdalen, which was later placed in the Baptistery.

Donatello maintained a lifelong friendship with the wealthy and famous de Medici family and upon his retirement received from them an allowance to live on for the rest of his life.

The artist died on December 13, 1466 of unknown causes. Donatello's unfinished work in Saint Lorenzo, Florence was completed by his student, Bertoldo di Giovanni. The works - two bronze pulpits - remain today as evidence of Donatello's deep understanding of suffering, darkness and the human experience.

Donatello Style and Technique

Perhaps even more than a sculptor, Donatello was an innovator. His artistic techniques were copied repeatedly by his contemporaries and successors and still inspire artists today. He focused throughout his career on producing in his sculptures a strong cognitive appeal that has drawn attention and praise for centuries.

Early years:

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Donatello's youth was not spent watching and learning his craft. He preferred instead to take the basics he learned from the Stonemasons' Guild and expound upon them in ways that pleased him. He was apprenticed only briefly to Ghiberti, choosing to strike out on his own before age 17.

At the beginning of his career, Donatello was influenced mostly by sculptures he had seen. His first offerings, like David, were characterized by Gothic elements like long, graceful forms and ornamental detail. Works following shortly thereafter, such as St. Mark and St. John the Evangelist, show a decisive move away from the Gothic style toward a more classical technique.

Middle years:

As Donatello's career progressed, his style became much more dramatic and emotional. He drew heavily on reality for inspiration, determined to accurately reproduce suffering, anguish, joy and many other human emotions.

Donatello's famous St. George and the Dragon - a relief in which the dauntless St. George, astride his horse, plunges a spear into a dragon's chest - is one of the earliest reliefs of its kind and Donatello's first attempt to produce a three-dimensional effect on a flat surface. He later invented and perfected this technique, known as schiacciato, or shallow relief. Schiacciato caused a major stir in the art world and Donatello found himself much in demand. In 1443, he spent ten years in Padua as the head of a huge workshop.

Advanced years:

Donatello returned to Florence during his twilight years and spent his time on reliefs for various churches throughout the city, most notably San Lorenzo. When he became bedridden, his students completed his unfinished work, careful to preserve his signature style.

Donatello's final years saw him complete several wooden sculptures that were not particularly well received. St. John the Baptist, for example, was shunned for its apparent weakness and fragility at a time when marble was the favored sculpting medium. In Donatello's later works, however, there is evidence of the impending Mannerist movement: exaggeratedly long limbs and intensely emotional facial expressions.

Who or What Influenced Donatello

Donatello's first education came at the hands of the Stonemasons' Guild, where he learned sculpting basics and other crafts. By the age of 17, he was working with the bronze reliefs of the doors of the Florentine Baptistery.

Donatello's apprenticeship to Ghiberti likely influenced him a great deal as he developed his own personal style and technique. In particular, elements of Ghiberti's style, developed from the late Gothic movement, can be seen in Donatello's David: it has a dramatic posture and a young, almost giddy energy.

Donatello also spent years collaborating with contemporaries such as Brunelleschi and Michelozzo, masters who undoubtedly provided feedback and helped mold Donatello's personal style. Donatello's partnership with Michelozzo resulted in the invention of a special type of wall tomb that served as inspiration for later generations of Florentine artists.

However, Donatello was fiercely individual when it came to his own technique. It cannot be said that he was led or influenced significantly by any one artist. Instead, he drew inspiration from classical figures and nudes. Donatello's figures were starkly real and vividly emotional, and there is evidence that he studied the frescoes of Italian painter Giotto di Bondone.

Giotto revolutionized religious art with his emphasis on accurately reproducing life as it truly was, including everything from landscape to facial expressions. Donatello followed suit, producing multiple works that were and remain famous for their strikingly realistic humanity and strong psychological element.

Between 1411 and 1413 Donatello produced two outstandingly unique works in St. Mark and St. John the Evangelist. Both sculptures catapulted the artist to fame, but St. Mark in particular had a classical stance and an impressive size that gave it a breathtakingly heroic aura.

Donatello Works

Donatello Followers

Donatello proved quite popular with his contemporaries and successors alike. His methods were closely studied by some of the greatest masters of the Renaissance and beyond and it is an undisputed fact that Donatello was one of the most influential sculptors in Western art history. His work, characterized by utterly realistic human expression and movement and ingenious use of perspective, is universally regarded as something of a bridge from classic to modern art.

Among Donatello's most noted followers were his students, Bertoldo di Giovanni and Desiderio da Settignano and other sculptors such as Andrea del Verrocchio, Simone Fiorentino, Vecchietta, Michelozzo, Andrea del Aquila, Buggiano and Andrea Mantagna. Even painters studied his works, inspired by the striking realism he employed in crafting human subjects.

Donatello was the first sculptor to employ bronze as a sculpting medium, encouraging other artists to experiment with different materials.

However, Donatello's influence on the trio of masters that lived and worked mostly alongside him was surprisingly small. All three men - Ghiberti, Luca della Robbia and Jacopo della Quercia - staunchly maintained their own styles and there is nothing in their works to suggest Donatello's influence.

However, it remains impossible to underestimate Donatello's influence on Italian sculpture. In many ways, he breathed new life into the art, and quite a few of his techniques are still employed today.

After death:

Donatello left behind numerous works of artistic genius, many devoted followers and several students who went on to build on his style and lead the art world into the High Renaissance era.

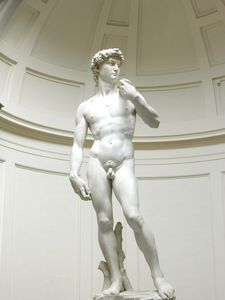

Donatello was the first artist to craft a nude sculpture and many followed his example after his death, including Michelangelo. Michelangelo's David, generally considered superior to Donatello's, followed in the same graceful, classical style. Donatello's influence can also be seen in Michelangelo's Bacchus, the Pietà in St. Peter's Basilica and Madonna delle treppe.

Donatello's influence was felt throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries by artists of various movements and mediums. In the sixteenth century his work was "rediscovered" by a small cadre of artists searching for inspiration. Those artists would later use Donatello's work as a basis for the founding of Mannerism, further enhancing Donatello's reputation as the artist responsible for bridging the gap between the classical world and the Renaissance.

Donatello Critical Reception

During life:

In his lifetime, Donatello enjoyed immense success and acclaim. Patrons scrambled to own one of his works and gave him commission after commission until he died at the age of 80. It is said that he produced more work in his lifetime than any of his contemporaries.

Donatello maintained a close and intimate friendship with the famously wealthy Florentine de Medici family until his death and constantly received commissions from Cosimo himself.

Noted Italians of the period such as Flavius Blondius, Bartolomeo Fazio, Francesco d'Olanda and Benvenuto Cellini all showered Donatello with praise. Even the poet and lyricist Lasca immortalized Donatello in verse, claiming that the artist did for sculpture what his contemporary Brunelleschi did for architecture.

Masaccio, widely regarded as the first great painter of the Renaissance, claimed to owe his knowledge of the classical style to Donatello, who helped lead him away from the fading Gothic tradition.

Donatello was unique in many ways but particularly for his universal demographic appeal. His works were lauded by all of Florence and indeed Italy. The poor peasantry and aristocracy both held him in high regard and it's likely that Donatello's name will be known and his influence on art will continue unabated for centuries to come.

After death:

The fact that Donatello's students so faithfully completed his work after his death is clear evidence of their devotion. Credited with bridging the gap between the classical and Renaissance worlds, Donatello forged a style and technique that was all his own and which continues to be well received centuries later.

Donatello's influence was felt in many facets of art, but in one controversial move he managed to take equestrian statues from the exclusive province of royalty and make them mainstream. Designed to echo the style and grace of the statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, Donatello's Gattamelata was a marble rendering of Venetian condottiere Erasmo da Narni.

Much like his predecessor, Giotto, Donatello's works inspired artists that followed him to experiment with space, perspective and depth. Donatello's technique for carving reliefs, known as schiacciato, revolutionized existing relief techniques.

Schiacciato, or shallow relief, was a way of carving marble so as to give a three-dimensional impression on a flat surface. In effect, Donatello made his figures and scenes come to life, an innovation that helped catapult the art world into the High Renaissance.

Donatello Bibliography

To learn more about Donatello please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Bennett, Bonnie A. & Wilkins, David G. Donatello. Moyer Bell Limited, 1985

• Janson, H. W. Sculpture of Donatello. Princeton University Press, 1979

• Lightbown, R. W. Donatello and Michelozzo: Artistic Partnership and Its Patrons in the Early Renaissance. Harvey Miller Publishers, 1980

• Lubbock, Jules. Storytelling in Christian Art from Giotto to Donatello. Yale University Press, 2006

• Poeschke, Joachim. Donatello and His World: Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance. Harry N Abrams, 1993

• Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Donatello: Sculptor. Abbeville Press, 1993

• Rea, Hope. Donatello. Forgotten Books, 2010

• Scott, Leader. Ghiberti and Donatello: With Other Early Italian Sculptors. Bibliolife, 2008