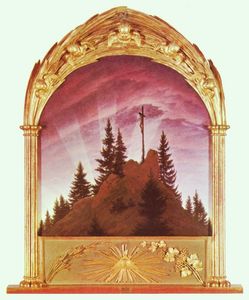

Cross in the Mountains

- Date of Creation:

- circa 1807

- Alternative Names:

- The Tetschen Altar, Das Kreuz im Gebirge

- Height (cm):

- 115.00

- Length (cm):

- 110.50

- Subject:

- Landscapes

- Art Movement:

- Romanticism

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Dresden, Germany

- Displayed at:

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Owner:

- Galerie Neue Meister

- Cross in the Mountains Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Cross in the Mountains Story / Theme

-

King Gustav IV Adolf

Gustav IV Adolf

Gustav IV Adolf was one of the earliest representatives of Romanticism on Europe's thrones and a foe of Napoleon who invaded Germany 1806. He won the affection of German patriots when he expressed his wish to see Germany restored to its former great nation and fame.

-

Cross in the Mountains

The 1805 sepia version of Cross in the Mountains caught the eye of Austrian royalty. Theresia Anna Maria Grafin von Bruhl, fiancé of Count Graf von Thun-Hohenstein, saw the sepia drawing at the Dresden show in March of 1807.

Smitten as she was by the piece, and always outspoken, she suggested that Friedrich execute it in oil. The couple had wished to purchase the 1807 oil version but Friedrich had other plans for his painting.

The future Countess wrote on August 1808 to her fiancé, "The beautiful cross is regrettably not for sale! The courageous Northerner has promised it to his king. " To her disappointment, Friedrich wanted to give Cross in the Mountains to his own sovereign; Swedish king Gustav IV Adolf who governed his native town of Greifswald.

Unfortunately, Adolf's political situations changed rapidly and by the time Friedrich completed the painting Gustav had been overthrown. The Countess ultimately succeeded in attaining her piece.

Friedrich wrote to his brother on November 25, 1808, "At Christmas I hope to receive two hundred thalers for a picture which is almost ready. " The altarpiece was purchased by the royal couple for the private chapel of their Tetschen castle.

Though this was his first major painting, Friedrich's intent here was the same as it was in a wide majority of his painting that would follow. He lined up with the dawning of new Romantic ideals, seeking to express the power of nature and illuminate the beauty and significance of Christ through nature.

The trees, mountains and rays of the sun all represent more than face value. They hint at the fortitude of Christ's love for mankind; an idea that was not yet used in landscape to express Christian ideals.

As Friedrich possessed a strong sense of German nationalism, this painting also served to express his political beliefs. The crucifixion represented Germany, who, now in the ruins from invasion, would, like the Christ figure, once again be restored.

Frame:

As this piece was intended as an altar piece, Friedrich took a special interest in the frame which was based on Friedrich's idea but carved by sculptor Gottlieb Christian Kuhn.

Cross in the Mountains Inspirations for the Work

Friedrich Said:

"One in everything and everything in one, God's image in leaves and stones, God's spirit in men and beasts, this must be impressed on the mind."

Friedrich said:

"Just as the pious man prays without speaking a word and the Almighty harkens unto him, so the artist with true feelings paints and the sensitive man understands and recognizes it."

The dawning Romanticism brought about a new art, faith and religious consciousness that inspired a unique search for God amongst 19th century religious painters.

Friedrich was one of the original artists to bring about these new religious beliefs that related art to faith. Inspired by both God and nature, Friedrich brought these ideas to life in Cross in the Mountains.

Original Inspiration:

First and foremost, Friedrich was inspired by images of God he saw in nature. For him, nature was the pictogram language of God.

Friedrich's greatest goal was to create something that could express the truth of God more clearly than the spoken word, even more clearly than poetry.

He took this inspiration and put it to canvas in his sepia version of Cross in the Mountains. It is safe to say that Friedrich was inspired and motivated by both religious and political aspirations.

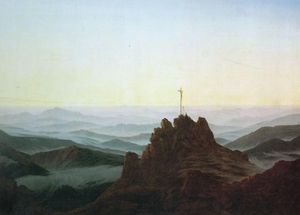

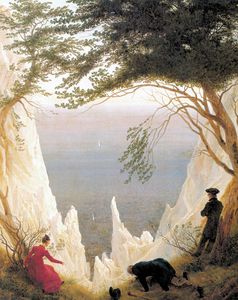

Proudly nationalistic, Friedrich drew aesthetic stimulation from German landscapes and his native Pomerania and the forest and peaks of the Riesengebirge mountains, southeast of Dresden, can be seen in this painting.

Cross in the Mountains Analysis

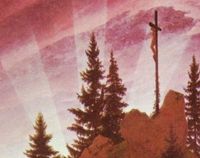

Friedrich used his first major painting, Cross in the Mountains as a platform to display both his religious and political standpoints. In a two-dimensional form, with a limited color palette and loose brushwork, the artist conjured up several feeling of religious piety and German nationalism in this canvas.

Composition:

The overall composition of Cross in the Mountains is two-dimensional. Its lack of definitive special depth adds to the mysticism of the painting.

The rocky pyramid, the tip of the trees and the expanding sun rays all seem to be pointing upwards toward the cloudy sky. The figure of the Christ, however, looks down at the setting sun. The viewer's standpoint remains unclear, yet his glance follows the triangle of the rock and the tip of the trees upward until it reaches the downward head of the statue.

Eye movement temporarily halts, stuck somewhere in the middle. At this moment the viewer can finally understand the magnitude of this painting and the artist's intent.

Frame:

The bottom of the frame is decorated with the "eye of God" and the symbol of the Trinity, with vines and ears of corn. On the side shapes resemble pillars with palm leaves that end in a pointed arch, studded with five angel heads. Above the middle angel is a silver star.

Color palette:

This painting was first a sepia drawing before executed in oil. The color is reminiscent of the sepia, still with deep reds and dark browns cast as shadows.

The setting sun adds a bit of brightness as the five rays expand to illuminate the dark sky and reflect upon the metal statue. The color of the sunset pokes out through the tree branches, forming a brief yellow horizon.

The viewer can imagine that just a few moments later, the sun would be completely hidden and the statue becomes even more obscure.

Use of light:

Cross in the Mountains is illuminated by five geometric rays formed by the setting sun. The two largest rays reside at the base of the left and right side of the mountain, rising about a third width of the mountain. The remaining three rise relatively equidistant from another but slightly off-centered.

The most significant of the three illuminates the statue on the cross, revealing slightly more than a silhouette. It is interesting that the artist chose five rays of sun and five angel heads to decorate the frame up above. Yet, only two of the rays and angels actually line up, so geometry and symmetry in this painting are randomized.

Tone elicited:

As a "neo-German, religious painting" this piece represented two things. As an altarpiece it could have invoked a somber tone, similar to the one a person experiences when walking into a church; holy and representing the piety of Christ.

It also served as a memorial to German power and strength. Like the overthrown Christ, Germany too would be resurrected to its original greatness. In this sense, the painting evoked a sense of nationalism for the anti-Napoleon Germans.

Brushstroke:

Overall, the brushwork of Cross in the Mountains is tight.

Cross in the Mountains Critical Reception

Cross in the Mountains received mixed reactions. Friedrich's loyal friends and supporters were counteracted by harsh critics who were appalled that the artist would consider a landscape as an altarpiece. If nothing else, the controversy it caused boosted Friedrich rise to fame.

During life:

When Friedrich opened his studio to the public during Christmas of 1808 Cross in the Mountains was met with both strong support and adamant disapproval.

Friedrich's friends and supporters were anticlassical and extreme nationalists and they defended the work against critics, the loudest being Wilhelm Basilius von Ramdohr, a pro-French lawyer and admirer of Napoleon and Neoclassicism.

He viewed the piece as a threat to the social values he cherished and his aesthetic dislikes clearly stemmed from political differences.

Von Ramdohr's main critique was that landscape could not allegorize a religious idea. He implied that the only way it was possible to find allegory in nature was if it was distorted, which he implied Friedrich did.

Responding to the controversy Friedrich wrote;

"Jesus Christ, nailed to the tree, is turned here towards the setting sun, the image of the eternal life-giving father. With Jesus' teaching an old world dies-that time when God and Father moved directly on earth. This sun sank and the earth was not able to grasp the departing light any longer. There shines forth in the gold of the evening light the purest, noblest metal of the Savior's figure on the cross, which thus reflects on earth in a softened glow. The cross stands erected on a rock, unshakably firm like our faith in Jesus Christ. The firs stand around the cross, evergreen enduring through all ages, like the hopes of man in Him, the crucified."

After death:

Cross in the Mountains is generally regarded as a masterpiece by modern-day critics for its ingenuity and for changing the idea of traditional landscape. This piece continues to travel to museums internationally.

Cross in the Mountains Related Paintings

Cross in the Mountains Artist

Friedrich gained great acclaim upon exhibiting Cross in the Mountains but this piece also caused much controversy as it was the first landscape to be considered in the genre of Christian art.

The attack of critics and the counter attack made by Friedrich's friends shone the spotlight on the artist but this was good practice for him, as he would have to endure a long career of being misunderstood.

The artist persevered, painting with his own religious and political convictions regardless of the reaction from critics.

To Friedrich, nature was not just a backdrop to fill the space behind portraits, for him nature itself took center stage. He sought the spirituality through the contemplation of nature, extending the bounds of trees, mountains, hills and crashing waves beyond just a beautiful view. They now had significant spiritual meaning.

Thanks to his intense and emotional focus on nature, Friedrich changed the style of landscapes and became a key member of the Romantic Movement. Friedrich helped shaped the movement while in its fledging stage, his personal ideals matching up perfectly with the new art form.

Neoclassical artists focused on properly accounting history through close attention to detail while Romantic artists flirted with themes of man's part in nature, divinity found in nature, and emotion.

Friedrich executed the divine in nature in his landscapes, specifically Cross in the Mountains which shows the details of Christ's crucifixion in an allegorical setting.

Although many critics are still unable to comprehend Friedrich's allegorical references to Christ and God through landscape, today his work is generally well respected.

Cross in the Mountains Art Period

Unlike most artists, Caspar David Friedrich took less inspiration for the great masters of art before him and paid more attention to the teachers of his formal education.

Consequently, Friedrich had a truly unique style; he could transform landscapes from a mere forest to a wooded wonderland where each branch symbolized something greater, something deeper. The trees were no longer just trees, but beautiful wooden creatures that represented the unwavering strength of Christ. The rays of the sun didn't just serve to illuminate the ground but to show the light of the Holy Father.

Unfortunately, Friedrich was largely misunderstood in his time and chose to paint for himself rather than to gain popularity. Artists of Friedrich's time could not grasp such a suggestive concept and so his followers were few.

He did, however, have a few loyal pupils but none that made a significant or memorable mark on the art world. Despite this, he had some admirers, including members of the Russian royal family.

Unfortunately, reception of Friedrich's work continued to deteriorate as he aged. Eventually even his patrons lost interest in his work as Romanticism was being replaced with new, modern ideals.

Friedrich died while his art was no longer wanted. Critics thought it too personal to understand, completely disregarding the fact that that was what made the work so original in the first place.

Symbolist and Surrealist artists, however, took note of the allegorical meanings that saturated Friedrich's canvases and both groups came to reference Friedrich as a great source of inspiration and foundation for their perspective movements.

Cross in the Mountains Bibliography

To find out more about Friedrich's contribution to Romanticism please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Barber, John. The Road from Eden: Studies in Christianity and Culture. Academica Press, LLC, 2006

• Bèorsch-Supan, Helmut. Caspar David Friedrich. Thames & Hudson, 1974

• Boime, Albert. Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815-1848. University of Chicago Press, 2004

• Hoffman, Werner. Caspar David Friedrich. Thames & Hudson, 2001

• Jensen, Jens Christian. Caspar David Friedrich: life and work. Barron's, 1981

• Koerner, Joseph Leo. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. Yale University Press, 1990

• Wintle, Justine. Makers of Nineteen Century Culture: 1800-1914. Routledge, 2002

• Wolf, Norbert. Caspar David Friedrich: 1774-1840: The Painter of Stillness. Taschen, 2003