Caspar David Friedrich

- Short Name:

- Friedrich

- Date of Birth:

- 05 Sep 1774

- Date of Death:

- 07 May 1840

- Focus:

- Paintings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Watercolor

- Subjects:

- Landscapes

- Art Movement:

- Romanticism

- Hometown:

- Greifswald, Germany

- Caspar David Friedrich Page's Content

- Introduction

- Artistic Context

- Biography

- Style and Technique

- Who or What Influenced

- Works

- Followers

- Critical Reception

- Bibliography

Introduction

Caspar David Friedrich changed the face of landscape paintings with his intense and emotional focus on nature, and became a key member of the Romantic Movement.

As Romanticism called for, Friedrich demonstrated piety to God through nature, the diminished strength of man in the larger scale of life, and great emotion.

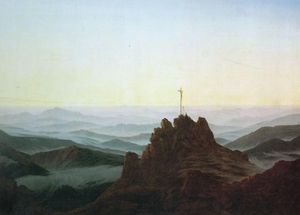

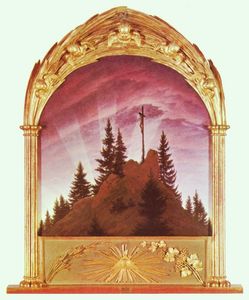

Some of Friedrich's best known works and most easily recognizable paintings include Cross in the Mountains (The Tetschen Altar), Wanderer above the Sea of Fog and Two Men Contemplating the Moon. In such paintings the artist's mood and love of nature cannot go unnoticed.

To Friedrich, nature was not just a backdrop to fill the space behind portraits, for him nature itself took center stage. He sought the spirituality through the contemplation of nature, extending the bounds of trees, mountains, hills and crashing waves beyond just a beautiful view. They now had significant spiritual meaning.

Sadly, Friedrich was, for the most part, misunderstood in his time. As an artist, he struggled to gain full comprehension from the public and critics of his time, but he continued to paint according to his own artistic convictions, not for approval. He experienced a significant amount of success during his high days, even being commissioned by the Russian royal family.

Many critics attacked his work, unable to comprehend his allegorical references to Christ and God through landscape but he was only known to defend his work on one occasion.

Today, however, his work is regarded positively and he is recognized as the true innovator he was. He is remembered as one of, if not the greatest, German Romantic painters.

Caspar David Friedrich Artistic Context

Unlike most artists, Caspar David Friedrich took less inspiration for the great masters of art before him and paid more attention to the teachers of his formal education.

Consequently, Friedrich had a truly unique style; he could transform landscapes from a mere forest to a wooded wonderland where each branch symbolized something greater, something deeper.

The trees were no longer just trees, but beautiful wooden creatures that represented the unwavering strength of Christ. The rays of the sun didn't just serve to illuminate the ground but to show the light of the Holy Father.

Unfortunately, Friedrich was largely misunderstood in his time and chose to paint for himself rather than to gain popularity. Artists of Friedrich's time could not grasp such a suggestive concept and so his followers were few.

He did, however, have a few loyal pupils but none that made a significant or memorable mark on the art world. Despite this, he had some admirers, including members of the Russian royal family.

Unfortunately, reception of Friedrich's work continued to deteriorate as he aged. Eventually even his patrons lost interest in his work as Romanticism was being replaced with new, modern ideals.

Friedrich died while his art was no longer wanted. Critics thought it too personal to understand, completely disregarding the fact that that was what made the work so original in the first place.

Symbolist and Surrealist artists, however, took note of the allegorical meanings that saturated Friedrich's canvases and both groups came to reference Friedrich as a great source of inspiration and foundation for their perspective movements.

Caspar David Friedrich Biography

Von Schubert (a philosopher and friend of Friedrich's)

"He was indeed a strange mixture of temperament, his moods ranging from the gravest seriousness to the gayest humor ... But anyone who knew only this side of Friedrich's personality, namely his deep melancholic seriousness, only knew half the man. I have met few people who have such a gift for telling jokes and such a sense of fun as he did, providing that he was in the company of people he liked."

-

-

Friedrich experienced a life of up and downs; his life began and ended harshly with a few happy years in between.

Early Years:

Young Friedrich did not have the carefree childhood most people enjoy. Before the age of thirteen he had witnessed the death of his mother, sister and favorite brother who had risked his own life to save Friedrich during an ice-skating accident.

Many art historians and psychologists believed that such events greatly impacted the content of his art and shaped him into the emotional painter he was known to be. His love of landscapes was evident early on in his career and his work demonstrated his belief in the power of God through nature.

Middle Years:

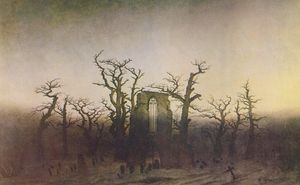

Shortly after gaining recognition for winning the Weimar competition, Friedrich exhibited his first major painting, The Tetschen Altar or The Cross in the Mountains in around 1806. It caused widespread controversy for its religious confusion; Friedrich kept the crucifixion of Christ as a background detail to serve the greatness of the landscape.

He was elected member of the Berlin Academy but never received full professorship, believing his political standpoint (anti-French/Napoleon) held him back.

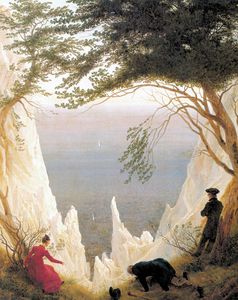

In 1818 Friedrich married Caroline Bommer with whom he had three children. Their union might have inspired a brief newness in the artist's style which drew the attention of the Russian royal family who provide a loyal patronage to the artist for several years.

He lost his patrons however as his happiness was replaced with his obsession of death and the afterlife.

Advanced Years:

Friedrich suffered a stroke that left him slightly debilitated in his hand. As a result, he painted predominantly in water color and sepia ink. However, his work fell from popularity and shortly afterward he died in 1840.

Caspar David Friedrich Style and Technique

In his sixty-six years of life, Caspar David Friedrich experienced several noticeable changes in painting style. Most notably, the canvases of his early years focused mainly on landscapes and in his mature years gravitated more towards humans, and his colors appeared brighter.

His work took a turn in his later years and his once inquisitive respect for nature was replaced by a bleak palette centering on death.

Early Years:

In his early years, Friedrich experimented briefly with sculpture at the Academy of Copenhagen but this was a short lived phase. After moving to Dresden he continued to experiment in other mediums and for a brief time he dabbled in printmaking, specifically etchings and he even tried woodcutting.

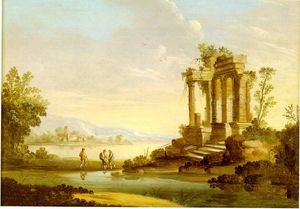

He later moved on to work in ink, watercolor and sepias. Friedrich continued to work in these mediums for the majority of his early career. It wasn't until 1797 with Landscape with Temple Ruins that he tried oil.

Middle Years:

As he matured Friedrich painted more in oils and some art historians attribute the change of style in his mature years to his marriage to Caroline Bommer, specifically after their honeymoon.

It is surmised that he added more figures to his landscapes than before because he realized the importance of human life, family and friends. The normally sullen artist pursued a new sense of happiness.

The painting Chalk Cliffs on Rugen was painted in 1818, the same year of his marriage and this piece depicts the couples' union. With the inclusion of people, the overall tone of Friedrich's work during this time had a new sense of levity and a brighter palette.

Regarding technique, Friedrich often used the "Rückenfigur", a person seen from behind contemplating the view. This technique allows the viewer to take in the same sites and share the experience with the figure.

Advanced Years:

In his later career his style changed once again. No longer displaying the beauty of God through his landscapes, Friedrich now focused on death.

The artist's happiness soon faded as he became "obsessed" with the afterlife. His style displays an overwhelming sense of loneliness and it seems the melancholy of his childhood had came back to haunt him.

As a result of the stroke he suffered in 1835, Friedrich lost some ability in his painting hand. Painting in oil became increasingly difficult and he was mostly limited to sepia and ink.

Landscape with Grave, Coffin, and Owl, executed just a year after his stroke is another example of the alteration in his style; he uses pencil and sepia, fitting mediums for this dreary theme of death. The palette is dark and muted and the questioning of life and fascination with nature is long gone in this canvas.

Who or What Influenced Caspar David Friedrich

Unlike most artists, Caspar David Friedrich took less inspiration for the great masters of art before him and paid more attention to the teachers of his formal education.

Though his teachers were not well known, they inspired in young Friedrich the love of nature and ability to see God in nature. He combined what he learned from each of them to form his signature; to express God's divinity through nature.

Hometown influences:

In 1790 Friedrich began his private studies at the University of Greifswald under the tutelage of Johann Gottfried Quistorp who taught him to draw from life outdoors.

Equally important was his introduction to another particularly significant influence; Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten. Kosegarten was a theologian who believed nature was a revelation of God. This idea coincided particularly with the ideals of the budding Romanticism, and can be seen extensively in Friedrich's work.

Though his teachers were considered masters of Danish Neoclassicism, they instilled in Friedrich the concepts of early Romanticism.

Although Friedrich's artistic influences helped develop his love for the outside world, nature and God in nature, he did not directly gain from their styles. After reaching maturity, Friedrich competently created his own themes and techniques and revived an interest in German landscapes.

Greater known influences:

Though their styles differed greatly, Friedrich, J. M.W. Turner and John Constable were all indirectly influenced by another. As Romantic landscapists, each artist grew up during a time when there was a growing disillusionment of an over-materialistic society. This churned in each artist a new appreciation for spiritualism and an increased interest in nature.

Born just a year apart, Turner and Friedrich often painted mountains surrounded in a mist or haze, a favorite scene among romantic landscape artists.

The difference between the two artists, however, is that Friedrich paid a careful attention to the details of an almost Neoclassical landscape technique while Turner painted in a crazy swirl, completely devoid of any technicality his classical training may have granted him.

Some critics say that because of this, Turner's art is more advanced and well ahead of its time in comparison to Friedrich's. Although Friedrich's art is allegorical, they believe he paints in a highly traditional matter.

Constable paints humbler realities though there is a presence of spiritual reality, as seen in Constable's Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows. Both Friedrich and Constable show visionary qualities.

Caspar David Friedrich Works

Caspar David Friedrich Followers

During life:

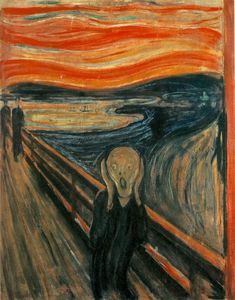

For the most part, Friedrich remained relatively misunderstood during his time but the turn of the century brought a revived interest in Friedrich's work as Norwegian art historian Andreas Aubert rediscovered his landscapes.

Aubert's writing caught the attention of the Symbolist painters, a budding new group of artists who could identify with his representative landscapes.

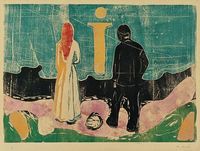

Edvard Munch was included in the painters inspired by Friedrich and his 1899 The Lonely Ones is homage to Friedrich's Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon.

Friedrich also influenced the Surrealist movement. Fellow German artist, Max Ernst, introduced Friedrich to his Surrealist acquaintances. Belgian surrealist, René Magritte was also known to reference Friedrich.

Friedrich was later featured in a Surrealist journal which exposed his work to a greater audience.

After death:

A more recent artist said to have admired Friedrich is Thomas Kinkade. Compare Kinkade's Sunrise with Friedrich's Cross in the Mountains or Morning in Riesengebirge and it is not hard to see the uncanny similarities.

The major difference between Kinkade and his inspirer is that Kinkade has found enormous success through his landscapes which seek virtues of a simpler lifestyle and his spiritual themes.

Caspar David Friedrich Critical Reception

During Life:

Friedrich executed religious and spiritual themes through landscapes. The Cross in the Mountains, an altarpiece, was his first work shown to a large audience and it was coldly received.

Critics were outraged that Christ's crucifixion cross remained an afterthought to the landscape instead of the focal point it had been in traditional art. For the first time in Christian art nature dominated the scene.

Friedrich's friends rose to his defense and he himself defended The Cross in the Mountains in a commentary a year later. He compared the sunrays to the light of God saying the painting represented man's continuous faith and hope in Jesus Christ still amidst the decline in formalized religion.

Regardless of public opinion of the work, the controversy it stirred increased Friedrich's popularity.

Despite the overall lack of understanding of his allegorical landscapes by the general public and critics alike he had several faithful patrons in his middle years, including members of the Russian Royal family. Unfortunately, reception of his work continued to deteriorate as he aged.

After Death:

20th Century:

During the 1930s the work of Friedrich took another unfortunate turn. Due to its blaring sense of German nationalism it was used as Nazi propaganda. Because of such strong associations Friedrich's art declined in popularity and was viewed with disdain.

It wasn't until art critics Werner Hofmann, Helmut Borsch-Supan and Singrid Hunz defended his work against political associations that his art was freed from Nazi chains. Finally, by the 1970s his work was being displayed in galleries and receiving new favor.

21st Century:

Today Friedrich's work is generally well respected as a great contribution to German Romanticism. He is remembered for his innovative way of changing the style of landscapes.

Caspar David Friedrich Bibliography

There are many books that have been written about Romanticism and Caspar David Friedrich's contribution to this exciting movement. To find out more please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Barber, John. The Road from Eden: Studies in Christianity and Culture. Academica Press, LLC, 2006

• Bèorsch-Supan, Helmut. Caspar David Friedrich. Thames & Hudson, 1974

• Boime, Albert. Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815-1848. University of Chicago Press, 2004

• Hoffman, Werner. Caspar David Friedrich. Thames & Hudson, 2001

• Jensen, Jens Christian. Caspar David Friedrich: life and work. Barron's, 1981

• Koerner, Joseph Leo. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. Yale University Press, 1990

• Wintle, Justine. Makers of Nineteen Century Culture: 1800-1914. Routledge, 2002

• Wolf, Norbert. Caspar David Friedrich: 1774-1840: The Painter of Stillness. Taschen, 2003