Rosso Fiorentino

- Full Name:

- Giovanni Battista di Jacopo

- Short Name:

- Rosso

- Alternative Names:

- Il Rosso

- Date of Birth:

- 1494

- Date of Death:

- 1540

- Focus:

- Paintings, Drawings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Wood, Stone, Other

- Subjects:

- Figure, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Mannerism

- Hometown:

- Florence, Italy

- Rosso Fiorentino Page's Content

- Introduction

- Artistic Context

- Biography

- Style and Technique

- Who or What Influenced

- Works

- Followers

- Critical Reception

- Bibliography

Introduction

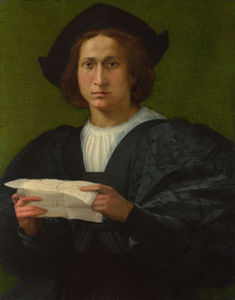

Giovanni Battisto di Jacopo, known throughout his artistic career as Rosso Fiorentino (the red-headed Florentine), was an artist of diverse talents with a completely unique way of seeing the world.

Fiery, restless and imaginative, Fiorentino made no shortage of enemies, yet inspired awe and respect wherever his travels took him as his talent and foresight was undeniable, not to mention his charm, grace and good looks.

As his contemporary Giorgio Vasari put it, "he was a man of splendid presence, with a gracious and serious manner of speaking, a good musician, and with a knowledge of philosophy. "

Fiorentino almost single handedly pioneered a new movement in art known as Mannerism, and though he was derided by art critics for centuries afterwards, he has in modern years finally garnered the accolades he deserves along with the recognition as a rebel before his time.

Fiorentino was unafraid to take conventions established by the Renaissance and turn them upside down, linking him with maverick talents of the modern era, from Surrealists to Abstract Expressionists.

Rosso Fiorentino Artistic Context

Mannerism was a period of European art history that followed closely on the heels of the Renaissance movement. While some critics consider Mannerism as part of the Late Renaissance, others classify this as a distinct period occurring between 1520 and 1600 that represented a break from many of the artistic values of the Renaissance, as naturalism gave way to the surreal.

Vasari, perhaps the most prominent art historian of the age, held Fiorentino in high regard, calling him a "man of splendid presence, with a gracious and serious manner of speaking, a good musician, and with a knowledge of philosophy.

He had only positive remarks about the majority of Rosso's works, except that produced during his time in Rome, stating: "it may be that with the air of Rome and the astounding things that he saw, the architecture and sculpture and the pictures and statues of Michelangelo, he was not himself. "

Vasari's inclusion of Fiorentino in his "Lives of the Artists" is one of the primary documents of Fiorentino's life and works, written by a contemporary who clearly deeply admired him.

The perception of not only Rosso Fiorentino but other Mannerists that followed, has fluctuated over the centuries, and only relatively recently have they been seen in a positive light. Fiorentino in particular was criticized for the contorted poses of his figures, as well as the fact that they often appeared somewhat thin, haggard, or skeletal.

Fortunately, in the 1950s art critics and historians started to see the Mannerists, including Fiorentino, in a different light. In fact, they did an about face in their stance on the movement, praising Mannerism for the traits they had previously counted as disabilities.

Fiorentino, with his distorted use of space and elongated figures, desire to shock and rebel against the accepted standards of the day, seems to have more in common with Modern artists than the Renaissance artists of the time.

Rosso Fiorentino Biography

Early years:

Born in Florence at the tail end of the 15th century, Rosso Fiorentino, given the birth name Giovanni Battisto di Jacopo, exhibited a wild talent from a young age.

Though his headstrong personality prevented him from joining the ranks of successful apprentices for a while, by the age of 17 he managed to enter the workshop of a certain successful painter, Andrea del Sarto.

During this time, working with another young and similarly ambitious contemporary named Jacopo Pontormo, Fiorentino helped develop a unique and abrasive new style of painting which came to be known as Mannerism.

Middle years:

After a few years of mild success and modest commissions Fiorentino's restless nature kicked in and he went to Rome to try to rival the work of the great masters. There, he took cues from the most up to date work that Michelangelo had completed on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, along with the latest portraiture of Raphael.

This was reflected in his own works from this time period, though Fiorentino managed to alienate himself from the masters themselves due to his outspoken manner.

After the Sack of Rome in 1527, Fiorentino was imprisoned along with many other citizens of Rome. Breaking free after a spell of humiliating manual labor, he spent the next few years aided by friends wandering from town to town in search of commissions.

Eventually he caught the eye of King Francois I of France, who, in being restored to his rightful position after years of captivity under the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, wished to highlight his strength in any way possible, including the artistic realm.

Francois lured a number of displaced Italian artists back with him to a hunting lodge in the woods deemed "Fontainebleau" and proceeded to let them, headed by Fiorentino, run wild with their imaginations in the refurbishing and decoration of the palace. Fiorentino was given a lavish suite and his own servants, along with complete artistic freedom.

Advanced years:

He lived out his final years in splendor and wealth in France, before allegedly committing suicide due to a misunderstanding with a friend in 1540 at the woefully young age of 45, at the height of commercial and critical success.

Rosso Fiorentino Style and Technique

Fundamentals of early Mannerism:

Fiorentino's style changed throughout the years along with his location. Continuously inspired by new surroundings and influences, he churned out a wide variety of work in his heyday. However, a few characteristics are maintained throughout his body of work.

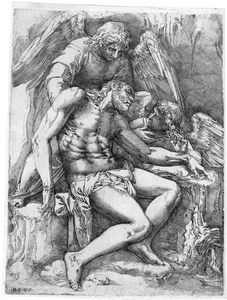

In a Fiorentino painting, the lighting is harsh, the figures tend to be angular and elongated, perspective is often from an unusual angle and the colors are brilliant though impetuous and limbs are elegant, tapered, and heads are often disproportionately small.

Fiorentino's Roman Influences:

There is an emphasis on raw emotion in Fiorentino's early works, which is toned down in his later period. After absorbing the Roman culture, a change can be seen in his paintings.

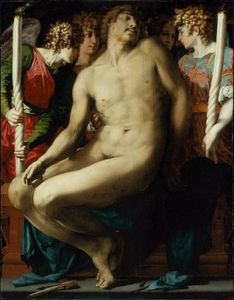

Works such as Dead Christ with Angels utilize increasingly classical forms, more harmonious colors and figures that take on a greater three-dimensionality, and sense of harmony rather than discord.

The School of Fontainebleau:

In order to produce the kind of work that would please the French court, Fiorentino drew on his former work but tweaked it to suit the more decadent aesthetic that befits a palace rather than a church.

More ornamental and decorative than his previous efforts, Fiorentino was given the freedom to unleash his imagination and create an entirely new spin on interior decoration.

New techniques utilized:

Leaving a greater legacy than his works that survived over the years at Fontainebleau were the innovative techniques that Fiorentino helped to pioneer.

One of these techniques was his strapwork, in which he molded plaster and stucco as if they were paper or leather, into curlicues and other intricately composed arabesques. These ornamental touches were utilized to frame frescoes and paintings, for the most part.

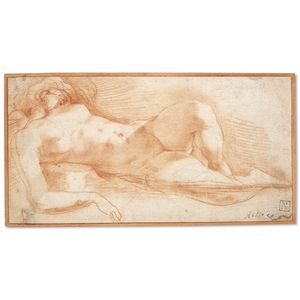

In addition, Fiorentino produced a multitude of sketches during his Fontainebleau tenure, which after his death were used by artists to create a series of etchings, a manner of reproduction that was quicker and more effective, and possessed greater fluidity.

Who or What Influenced Rosso Fiorentino

Growing up in Florence at the turn of the 16th century, it was most likely difficult not to be influenced by the proliferation of art and artists that abounded at the time.

Fiorentino had the privilege of seeing works by artists such as Michelangelo as they were being created, and to learn about the process through this observation. The form of painting had reached a hitherto-unknown height of realism, and the Renaissance had come into its own.

Although Fiorentino drew on many sources in the development of his own style, the works of Michelangelo are most apparent in his early paintings, along with the study of Gothic engravings.

Later on, Michelangelo's advanced works as well as the refined style of his fellow Mannerist, Parmigianino, helped to influence the maturation of Fiorentino's style.

Michelangelo:

While Michelangelo was certainly an influence on a great many artists during this time, his influence is especially apparent in the work of Fiorentino. His attention to anatomy, exceptional realism, and complex positions of figures are all evident in Fiorentino's early works.

Rosso Fiorentino was impressed by the grandeur, humanity and nobility of Michelangelo's oeuvre and similarly tried to impart a timeless sense of importance and drama to his own works.

In his work at Fontainebleau Fiorentino shows a clear understanding of Michelangelo's designs for the Medici Chapel, executed between 1519-1534. This work of Michelangelo's featured elegant figures in unnaturally twisted poses set within a complex architectural framework.

This would be repeated by Fiorentino in the complex multimedia arrangements inside the Palace.

Gothic Engravings:

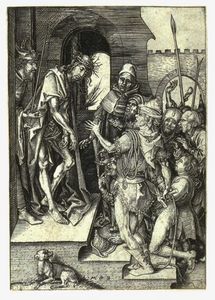

During the latter part of the 15th century - the later Gothic years - artists had developed a remarkable level of realism, symbolism and intricacy. This was seen in their engravings, which depicted both allegorical and everyday scenes.

Fiorentino appears to have drawn mainly from two artists known for their detailed engraving work, Martin Schongauer and Albert Durer. Both utilized a deviation in compositional style and Durer in particular was interested in showing the ugly, horrific and unique in nature, far from the idealizations that Renaissance artists in Italy were creating.

Parmigianino:

While in his earlier works Fiorentino favored dissonant colors, angular figures and a harsh range of emotion, in his intermediate period in Rome he tempered this after viewing the works of other contemporary Mannerist painters such as Parmigianino.

Parmigianino favored a lengthening of limbs and distortions towards a greater manifestation of elegance, and a quiet dignity pervades his paintings.

Rosso Fiorentino Works

Rosso Fiorentino Followers

As one of the founders of Mannerism, Fiorentino left a lasting legacy in the art world, spawning a generation of imitators. From fellow Italian Mannerists such as Franco and Tintoretto, to those who were influenced by his style in France at Fontainebleau, all facets of his career have been drawn on by other painters, both contemporaries and modern artists.

Francesco Primaticcio:

Primaticcio was a fellow Italian who joined Fiorentino at Fontainebleau and helped found the elaborate decorative style so prominent there. Indeed, he took over from Fiorentino after his death in 1540 and became the head of the Fontainebleau School.

Fiorentino's influence is clear in Primaticcio's crowded and elaborate compositions and long-limbed, elegant figures. Beyond painting, Primaticcio also helped design masks and costumes for elaborate balls, as well as the stucco work and architecture of Fontainebleau.

Primaticcio's own influence was evident in French art for the remainder of the decade.

Jean Mignon:

Another Fontainebleau artist, he worked from the years 1537-1540, as an apprentice directly under Fiorentino. During this time, he crafted his own fascinatingly ornate set of paintings and engravings.

Most of his work drew on mythological or religious themes, as Fiorentino's did. Mignon tended to place his figures in incredibly elaborate settings, with the figures posed in stiff, unnatural positions, typical of Mannerism.

It has been said that these fantasy worlds he created became completely unreal, a testament to cold beauty, almost as if all the figures had been turned to stone.

Overall he produced some of the most memorable work at Fontainebleau during his short time there.

Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti):

A Venetian artist who trained briefly with Titian, Tintoretto is most well known for his extremely complex compositional arrangements. It is said that he would make wax models of the figures in his paintings and arrange them on a stage to view the effects of changes in light, color and tone before painting.

Though an individualist, it is clear that the early works of Fiorentino had an effect on Tintoretto's art.

Ambroise Dubois:

A Flemish painter who moved to France at the end of the 16th century, Dubois was one of the members of the Fontainebleau school that succeeded Fiorentino. Dubois took over during the later years to form the second school of Fontainebleau.

These artists drew on Fiorentino's example in their highly stylized forms and elegant figures, but added a greater depth of composition, brighter, bolder, richer colors, and a greater contrast between light and dark that would herald the impending arrival of the Baroque.

Battista Franco Veneziano:

Born in 1510, Franco studied in Rome, where he was influenced by the works of Michelangelo as well as the Mannerist leanings of Fiorentino. He worked with Vasari on some large decorative works and painted a series of portraits of the Medici family, but is best remembered for his engravings.

In the elongated figures, odd lighting effects and complicated positioning of objects in his compositions, Fiorentino's influence is clear. Indeed, he executed a series of direct copies of Fiorentino's works. In fact, only about half of Franco's works are originals.

Rosso Fiorentino Critical Reception

Public opinion

Much of Rosso's work was lost or destroyed, with only a few actual paintings remaining for public view. The work that art historians almost unanimously agree is his masterpiece, Deposition from the Cross, is unfortunately located off the typical Tuscan tourist path of those headed to Florence or Siena, meaning that a great portion of the art-loving public misses it. The inaccessibility of Fiorentino's works has rendered this great painter an also-ran next to the more famous names of his time.

-

-

Always a volatile and controversial character, the critical and public perception of Fiorentino's work has fluctuated throughout the ages, falling in and out of favor.

While during his lifetime Fiorentino managed to find a relative degree of fortune and success, more specifically during his days at Fontainebleau, in the following years his work became unfashionable, along with Mannerism in general.

Early criticism:

During his lifetime, Fiorentino received his fair share of criticism, though as he set tongues wagging with his rogue-ish behavior, his star power only increased exponentially.

His reception in Florence during his youth was not of the most desired kind, with a lack of appropriate commissions and a corresponding lack of money or success.

With his earlier works, such as The Assumption of the Virgin painted in 1517, the drastic departure in style from earlier Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo, assured that the critics viewed his paintings with misunderstanding and even disdain.

The angularity of Fiorentino's figures, the almost aggressively dissonant and disturbing use of light and color, and the over-emotional aspect of the bizarre compositions all helped to alienate contemporary viewers.

Later criticism:

As Fiorentino tempered his style and produced more crowd-pleasing works in his later years in Rome and then eventually at Fontainebleau, art critics gave him more credit and the offensive peculiarities of his style that had been previously picked up on were seen as benefits.

A Fiorentino piece is easily identifiable if nothing else, despite having spawned a flurry of imitators. A greater appreciation for his wit and accelerated techniques developed over time.

Modern critics:

For centuries Mannerist painters, particularly Fiorentino, were dismissed as pale imitators of Renaissance masters. It was said that they took something essentially perfect and twisted it into something overly stylized and grotesque.

Fiorentino in particular was criticized for the contorted poses of his figures, as well as the fact that they often appeared somewhat thin, haggard, or skeletal.

Fortunately, in the 1950s art critics and historians started to view Mannerism in a different light. Fiorentino, with his distorted use of space, elongated figures and desire to shock and rebel against the accepted standards of the day, seems to have more in common with Modern artists than the Renaissance artists of the time.

This may be why the work of Mannerists experienced a renewed sense of fascination and respect in modern times that has persisted until this day.

Rosso Fiorentino Bibliography

To find out more about Rosso Fiorentino and the Mannerist era please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Carlo, Falciani. Il Rosso Fiorentino. Olschki, 1996

• Carroll, Eugene A. & Fiorentino, Rosso. Rosso Fiorentino: Drawings, Prints, and Decorative Arts. National Gallery of Art, 1987

• Franklin, David. Rosso in Italy: Italian Career of Rosso Fiorentino. Yale University Press, 1994

• Letta, Elisabetta M. Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Scala Riverside, 2001

• Natali, Antonio. Rosso Fiorentino. Silvana, 2007

• Vasari, Giorgio. Lives of the Artists: A Selection. Penguin Classics, 1987