John Singer Sargent Critical Reception

- Full Name:

- John Singer Sargent

- Short Name:

- Sargent

- Date of Birth:

- 12 Jan 1856

- Date of Death:

- 14 Apr 1925

- Focus:

- Paintings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Watercolor

- Subjects:

- Figure, Landscapes, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Realism

- Hometown:

- Florence, Italy

- John Singer Sargent Critical Reception Page's Content

- Introduction

- During Life

- After Death

Introduction

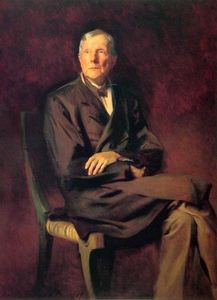

At the height of his career from the 1890s to 1910, Sargent commanded a great deal of money for his portraits. Many of his American clients traveled to his studio in London at their own expense to have their portrait painted by him. Despite this, some history books state that Sargent is "often passed by, not studied, or dismissed. " Until recently, he was regarded as a relic of the Gilded Age, but recent scholarship has strengthened Sargent's reputation.

John Singer Sargent During Life

John Singer Sargent began receiving extremely positive critical reception before his career had even started. His remarkable technical skill and perfect French made him the 'darling' at Paris's most prestigious art school. His submissions to the school's esteemed Salon won praise and recognition year after year. The writer Henry James wrote that the artist offered "the slightly uncanny spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn. "

Sargents' reputation soured drastically in 1898 following the submission of Madame X to the Salon, although not purely for stylistic reasons. The portrait was a sexually suggestive one of a prominent Parisian socialite named Madame Pierre Gautreau. Her chest is shockingly bare for the Victorian era.

In the original, the left shoulder strap hangs off to one side, making the effect more provocative and daring. In an attempt to placate the scandalized Parisian society - and the girls' mother - Sargent altered the hanging strap, but the damage was done. Sargent moved to London soon afterwards.

In London Sargents' paintings were not initially well-received. Like the Parisians, Londonites considered his compositions eccentric and added the label "Frenchified" to boot. However, one of his sitters, Mrs. White, took Sargent under her wing and helped him to penetrate British art society and receive portrait commissions. Sargent won over the British art world with his submission of Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1886), a portrait of two little girls lighting Japanese lanterns.

For the rest of his life, until he officially gave up portrait painting in 1907, Sargent was in demand as the premier portrait painter by the rich and famous on both sides of the Atlantic. One art critic praised Sargent as "the unrivaled recorder of male power and female beauty in a day that, like ours, paid excessive court to both. "

Sargent was also honored with the ongoing commission of painting Judeo-Christian-themed murals for the Boston Public Library - a commission that was only supposed to last 10 years but, due to the library's' love of Sargent's work, lasted 29 instead.

After 1907, Sargent mostly painted watercolors of landscapes. Although he is not as celebrated or famous for these works, he did exhibit two major watercolor shows. Critics considered his style technically excellent. Moreover, there is a sense of joy in the work, as if the artist were painting purely for himself.

Towards the end of his life, most reviewers began to consider Sargent a master of the past due to his refusal to adopt the emerging artistic trends of Cubism and Futurism. Sargent did not deny the criticism but neither would he paint in any of the new Modernist styles. Ironically, Sargents' mural for the Boston Public Library, based on Classical scenes of art history with a few winking twists, was credited for being "the invention of a high order of originality. "

This last major work of his life was heralded as a success without precedent since the Renaissance. However, in 1925, the mural genre fell out of favor and from that point on, no one had a kind word to say about Sargents' mural.

John Singer Sargent After Death

Immediately following his death, Sargent was considered an anachronism of the Gilded Age who was out of step with current artistic trends. However, the lack of attention he was given in the decades immediately following his death is surprising even in light of this fact, considering the phenomenal, unsurpassed fame he achieved as the portrait artist of his day.

There are several theories for why this is so: Sargents' brilliance lay in combining styles, not in creating new ones. Therefore he is not studied because his work wasn't radical enough. His portraits of the upper-class are criticized as being shallow and self-absorbed, although his defenders point out that he was only painting what he saw, and in doing so, shining a mirror on the shallowness of the elite while at the same time being paid to do so.

Other theories relate to the man himself. Sargent was a Jewish man during a time of growing anti-Semitism. Following World War 1 Jewish prosperity was widely resented and Sargents' close association with the wealthy Jewish family, the Wertheimer, of whom he painted many portraits, did not help his reputation.

His personal life is also uninteresting: Sargent lived a quiet, scandal-free life and died with his successful career intact; therefore he is not interesting in the manner that Van Gogh was interesting. It is probable that Sargents' initially chilly post-humous reception is a combination of these three factors.

Modern Day Reception:

In the 1960s, a renewed interest in Victorian art and a subsequent reinvestigation of Sargent's work defended and strengthened his reputation. In 1986, the Whitney Museum held an exposition of his work. Later, in 1999, a traveling exhibition of Sargent's oeuvre was shown at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art Washington, and the National Gallery, London. With these exhibitions, John Singer Sargent has regained the respect and acclaim he deserves.