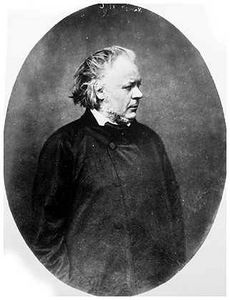

Honoré Daumier

- Full Name:

- Honoré Victorin Daumier

- Short Name:

- Daumier

- Date of Birth:

- 26 Feb 1808

- Date of Death:

- 10 Feb 1879

- Focus:

- Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings

- Mediums:

- Oil, Watercolor, Prints, Wood

- Subjects:

- Figure, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Realism

- Hometown:

- Marseille, France

Introduction

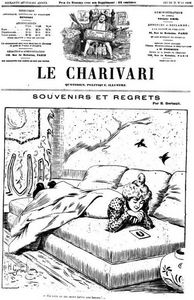

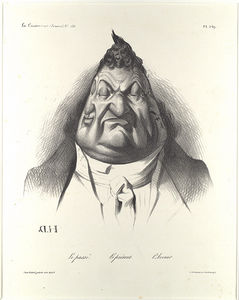

During the aftermath of the French Revolution, Honore Daumier, "the Michelangelo of caricature", rose to prominence as the caricaturist of 19th century French politics and society. His determined focus on the foibles of 19th century France make him the one artist who comes closest to summing up this part of French history. Forced to quit school at the age of 12, Honore Daumier developed a life-long sympathy for the poor. Unfortunately, he sympathized so much with them that he died in debt and was buried in a pauper's grave.

Honore Daumier used his skills as a lithographer to ridicule French government and society. In his youth, he even wound up in jail for a caricature of the French King. An extremely productive artist, he made almost 4,000 prints before going blind. He was also a talented painter and sculptor, but these works mainly became known after his death.

Honoré Daumier Artistic Context

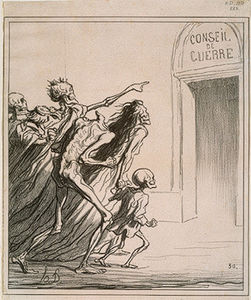

Honore Daumier lived in an age of dramatic political, economic, and social upheaval. During his lifetime, there were five major changes in government as his countrymen grappled with the aftermath of the 1789 French Revolution. The Industrial Revolution was also taking place during this time which served as a blow to the old social order, creating an entirely new class of impoverished industrial workers in the process. Against this backdrop, Honoré Daumier used his art as biting social commentary.

Honoré Daumier Biography

Early Years:

Honore Daumier was born in 1808 in Marseille, France. In 1816, his father moved the family to Paris to try his hand at poetry. His father did not achieve much economic success so at the age of 12, Daumier was forced to quit school and work at a bailiff's office. Witnessing the problems of those rifling in and out of jail imparted him with a life-long sympathy for the poor. At the age of 16, Daumier began receiving training in the art of lithography with Alexandre Lenoir and studying at the Academie Suisse.

Middle Years:

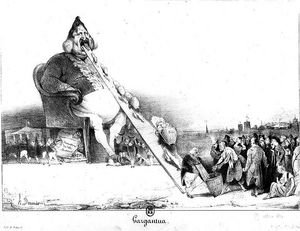

Honore Daumier used his print-making skills in several satirical publications of the era. During this period, this was a powerful social platform from which to influence the masses. In 1832, he published an offensive cartoon against the government and received a suspended sentence. Honore Daumier published another anti-governmental cartoon that was just as vicious and was jailed for six months. Afterwards, he only caricaturized the middle-class and particularly liked criticizing lawyers and the justice system.

In 1846, Honoré Daumier's son was born and he married the mother of the child, a 24-year -old seamstress shortly afterwards. Sadly, his son died two years later.

Later Years:

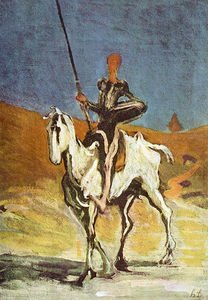

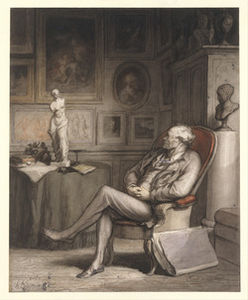

In his old age Daumier increasingly worked on his sculptures and paintings. His works were accepted to exhibit at the Salon four times but received little attention, although modern critics consider them to be ahead of their time. Daumier was particularly interested in the theme of Don Quixote and painted one iconic image of him riding off into the sunset. In 1878, a few months before his death, his friends rounded up a number of his paintings to be shown at Durand-Ruel's gallery. However, these works did not meet with much critical reception until after his death.

Honoré Daumier Style and Technique

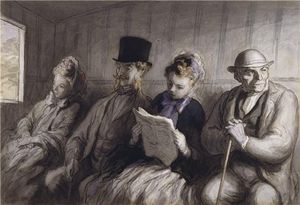

Honoré Daumier worked in a number of styles, depending on the medium. These styles are: caricature, naturalism and sculpting. Honoré Daumier was best known for his caricature works and he used the classic caricature techniques of physical absurdity to lay bare the cruelty, unfairness and pretension of 19th century French society and politics. After having worked as an assistant to a bailiff, he had a particular distaste for lawyers. The medium of lithography allows for quick, sketchy, images, which create a sense of movement - and also a sense of a candid moment. Critics described him as a master at recording the unrehearsed moments of daily life.

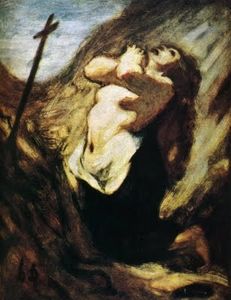

Daumier came to painting - and naturalism - fairly late in life and he painted religious as well as historical themes. If it were not for this inclusion of historical material, he would be considered purely a Realist. The naturalist philosophy believes in man's futility against nature and some of Daumier's religious paintings suggest this. He also used everyday subjects, such as The Laundress, to provoke discussion about wider social issues.

He was also interested in exploring literary themes, in particular the ones contained in the popular novel Don Quixote, the fool who thinks he's a hero as he, in the famous scene, battles windmills. Daumier also tried his hand at sculpting, which was not a popular form of art at the time. His sculptures are known for being remarkably life-like.

Who or What Influenced Honoré Daumier

Honoré Daumier's style is so much his own that it is not easy at first to detect the influence of other artists. However, three artists in particular have been identified as having a strong influence on Daumier's work.

Nicolas Toussaint Charlet (1792-1845):

Charlet was a fellow Frenchman and he shared the same humble background as Daumier as well as his empathy for the poor. Charlet was renowned for his lithographs but he was fluent in a number of mediums including watercolors, oil painting and sepia-drawings.

Charlet's lithographs deal with the same social and political themes that Daumier would later adopt. The height of his success came in the 1820s, at the start of Daumier's career and so he could not help but have been influenced by him.

Charlet's art looked to the past: the military glories of the Napoleonic wars and depictions of peasant life. In doing so, he fed the nostalgia of the French nation by providing a feeling of regret for the recent past, combined with a lingering dissatisfaction for the present. Like Charlet, Daumier was also a fan of Napoleon Bonaparte, a revolutionary and former ruler of France.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877):

Courbet was a contemporary of Daumier and is mainly known for courting controversy by addressing the same social issues that Daumier did in his lithographs. Courbet is considered the forerunner of the Realist movement, a movement that also bridged Impressionism. Instead of dealing with the perfection of line and form, the standard of the time, he painted in a spontaneous and rough style.

Courbet painted peasantry and depicted the working conditions of the poor and his painting techniques, along with his philosophy, are considered innovative. While painting historical scenes was the way to get ahead in Paris as an artist at this time, Courbet believed that an artist's own experience was the only thing he or she could accurately portray.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640):

Rubens was a seventeenth-century Dutch baroque painter whose works Daumier studied while training. The baroque style emphasizes movement, color, and sensuality. It was a reaction against the same old religious art work of the period. While the baroque movement dealt only with religious art, it dealt with it in a populist manner, which would have appealed to Daumier. Art work was now directed towards the illiterate, rather than the educated. The works were designed to have an emotional impact, much in the same way that Daumier intended in his works.

Rubens is best known for his masterful handling of light and ability to express color in subtle gradations. His drawings are precise and display technical skill, but they are not detailed, which was a pattern that Daumier was to follow. He was also a forerunner of the heavy, obvious brushstrokes which were di rigueur for Realists such as Daumier.

Honoré Daumier Works

Honoré Daumier Followers

Although he never made a commercial success of his art during his lifetime, Daumier was appreciated by artists with good taste. Those who collected his works include: Eugene Delacroix, Jean-Louis Forain, Charles Baudelaire, Edgar Degas and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. They admired him more for his lithographs than they did his paintings, because they considered the former to be more daring. Corot in particular was a good friend of Honoré Daumier. During his later years, when Daumier was destitute and without shelter, Corot bought him a cottage.

Honoré Daumier Critical Reception

Honore Daumier has been called the "Michelangelo of caricature" and his place in history as the caricaturist of 19th century French political and social history is assured. However, Daumier was much more than a caricaturist. His artistry spanned several mediums, which only began to be recognized after his death. In many ways, his artwork was both timeless and ahead of its time, which is why it continues to be appreciated to this day.

Contemporary Reception:

During his lifetime, Daumier was perceived as a thorn in the government's side. The bluntest form of critical reception the government gave him was jailing him in 1832 for a cartoon titled Gargantua. Gargantua depicted King Louis Philippe as a monster devouring his subjects. However, towards the end of his life, Daumier began to receive increasing respect from the government for his efforts in the form of commissions and committee appointments. And the common man did appreciate his efforts on their behalf.

Starting in the 1850s Daumier began receiving notice in Parisian reviews and exhibiting his art works in the Parisian Salons. A few months before his death, a retrospective exhibit took place.

Posthumous Reception:

The widespread recognition of Daumier's full artistic potential only began upon his death. His paintings were the first to be recognized: he is considered to have an unusually direct viewpoint, and admirably experimental techniques. Daumier's depiction of the foibles and hypocrisy of the upper-class is considered timeless.

Honoré Daumier Bibliography

Find out more about Daumier and his fascinating works by referring to the sources below.

Books:

• Armand Hammer Foundation. Honore Daumier: 1808-1879 The Armand Hammer Daumier Collection (1982)

• Bodkin, Robin Orr. Honore Daumier: the Early Lithographs (2005)

• Daumier, Honore. The Drawings of Daumier (1978)

• Laughton, Bruce. Honore Daumier (1996)

• Longstreet, Stephen. The Drawings of Daumier (1964)

• Symmons, Sarah. Daumier (2005)

• Wartmann, Wilhelm. Honore Daumier. 240 Lithographs Selected (1946)

Web Sources:

• http://www.daumier.org/1.0.html

• http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/daumier_honore.html

• http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Honore_Daumier.aspx