Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes

- Date of Creation:

- circa 1305

- Alternative Names:

- Arena Chapel

- Medium:

- Other

- Support:

- Other

- Framed:

- No

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Padua, Italy

- Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Story / Theme

The Scrovegni Chapel (often called the Arena Chapel for its original proximity to the ruins of a Roman arena) is universally accepted as Giotto di Bondone's masterwork. Completed in 1305 for the Enrico Scrovegni family in Padua, Italy, the frescoes adorning the walls and ceiling of the chapel relate a complex, emotional narrative on the lives of Mary and Jesus.

The genius of the Chapel lies in the narrative's layout: di Bondone arranged the different scenes chronologically, in horizontal bands. Mary's life appears first, followed by the life and ministry of Jesus, and finally culminating in scenes depicting the Passion. However, when the bands are read vertically, viewers will be struck to realize that each scene foreshadows the next.

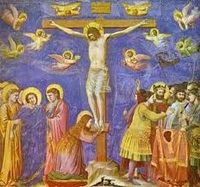

Among the Scrovegni Chapels frescoes are some of the most famous of di Bondone's work. The Lamentation, for example, a moving depiction of Christ's mourners surrounding him on the cross, is extremely well-known, especially for the raw emotion evident on the subjects' faces.

Other noted frescoes include Raising of Lazarus, Marriage at Cana, and Noli Me Tangere ("Do not touch me"). The Scrovegni Chapel, clear evidence of di Bondone's ability to use pictures to tell a complex story, has been preserved for over seven centuries and is today open to visitors in Padua, Italy.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Inspirations for the Work

Decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel was commissioned at the beginning of the fourteenth century by a wealthy Italian banker called Enrico Scrovegni. It was a family chapel, built, some believe, a restitution for Scrovegni's involvement in less-than-reputable dealings.

There is no evidence that Scrovegni suggested a theme to di Bondone; however, in keeping with the tenets of Catholicism (and asking forgiveness), di Bondone settled on a visual narrative of Christ's miracles and experiences on earth, a depiction of the life of the Virgin Mary (displaying in every scene her devotion, piety, obedience and ultimately her role in salvation for all humans), and, finally, the intertwinement of both lives and the Passion of Christ.

As a tribute to the Scrovegni family, in the Last Judgment fresco, Enrico Scrovegni himself is depicted presenting a model of the chapel to Mary.

As with most other works of art during the late Medieval period, di Bondone's known themes and settings are exclusively religious. Heavy emphasis was placed, at the time, on salvation and honoring the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ. The iconological source of the scenes depicting Mary, Jesus, and Joachim is most likely the Apocryphal Gospels.

Other probable sources include Franciscan devotional texts and literary works from the likes of Prudentius, Cicero, Bartolomeo da San Concordio and Seneca. It was originally thought that Dante's Divine Comedy inspired the depiction of Hell, but new information on the dates of Dante's work indicate this is not the case.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Analysis

As a whole, the Scrovegni Chapel is a model of artistic fluidity and visual storytelling genius. Di Bondone makes careful use of composition throughout the chapel to draw viewers' attention to desired points of focus, arranging his subjects in a way that ensures maximum emotional engagement.

Giotto's use of horizon lines, geographic forms and architecture within the scenes seem to have all been meticulously manipulated to point viewers in the desired direction.

Di Bondone's use of color is striking in the Chapel and in every other fresco he painted. Choosing to eschew the traditional golds and grays of religious imagery, he opted instead for a brighter, more realistic palette featuring blue skies, colorful clothing and multihued landscapes.

He also regularly used color to express emotion: reddened cheeks, dark skies, and brown foliage, for example. Di Bondone believed that life should be painted as it is, not in the highly stylized and unrealistic Byzantine method.

Illumination and shading are two of the most useful tools in di Bondone's toolbox. He used them repeatedly, both in the Scrovegni Chapel and elsewhere, to demonstrate a subject's importance (or lack of) and of course holiness. He also relied heavily on lighting and shade to draw attention to the main idea of the fresco, to give his human subjects more weight and shape, and to give the scene a more realistic feeling.

It was, finally, extremely important to di Bondone to adequately convey mood, tone and emotion in his frescoes. While in traditional religious paintings, emotions like joy, sorrow and anger were subdued at best, di Bondone maximized use of facial expressions, gestures and postures to communicate what the subjects were feeling.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Critical Reception

The Scrovegni Chapel was completed in around 1305 and proved an immense success. Pope Benedict XI had chosen to grant indulgences to those who visited, and thousands flocked to the site. Evidence suggests they were awestruck by what they observed: the bright, colorful, emotional frescoes decorating the inside of the chapel were unlike anything most of them had ever seen in a religious setting. Di Bondone's reputation as an artistic genius was solidified with the completion of the Scrovegni Chapel.

During life:

Lay people and artists alike could appreciate di Bondone's beautiful, moving work inside the Scrovegni Chapel. It received many thousands of visitors during di Bondone's life and had the blessing of Pope Benedict XI, who decreed that indulgences would be granted to those who made the journey to see the marvelous frescoes.

A group of Augustinian friars living at the nearby Eremite monastery, on the other hand, claimed that it was too big and luxurious for what was meant to be a simple family chapel, and also that the bells rang too loudly. It is likely that they feared the competition the new chapel would bring to their monastery and convent church.

After death:

Purchased by the city of Padua in 1880 and carefully restored throughout the following century, the Scrovegni Chapel has retained much of its original popularity for both tourists and artists. Pilgrims continued to visit after di Bondone died, perhaps no longer receiving indulgences but eager to see the masterwork of the most important artist of the past two centuries.

Tens of thousands of visitors behold its beauty every year, and it remains the ultimate symbol of Giotto di Bondone's massive contribution to the Renaissance.

Around one hundred years after di Bondone's death, artists of the emerging Renaissance began to seriously study and imitate his work at Scrovegni. Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Masaccio and Raphael all visited and studied the chapel at one time or another to glean the wisdom of their predecessor.

Thus, the Scrovegni Chapel has remained a symbol of artistic genius and innovation throughout the centuries and is one of the most celebrated works of art in the history of Western art.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Related Paintings

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

The Scrovegni Chapel began, naturally, as the property of the Enrico Scrovegni family of Padua. Enrico Scrovegni, a wealthy banker, had acquired the land for a song from Manfredo Dalesmanini, who was experiencing financial woes. Specifics about the chapel's ownership remain vague until the nineteenth century, when the owners of record were the Foscari Gradenigo family. They proved to be rather neglectful, allowing the portico to collapse before the city of Padua finally acquired the chapel in 1880. The building survived, albeit with serious damage to the frescoes and the building itself.

The Scrovegni Chapel underwent intensive restoration during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the frescoes today are clean and well-preserved. The chapel is now open to visitors, which come from all over the world to see the masterwork of the father of the Renaissance.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Artist

The Scrovegni Chapel is widely, if not universally, considered to be his masterwork, portraying scenes from the life of Mary and Jesus, along with scenes depicting miracles performed by Christ.

Di Bondone had reached the middle of his life by the time he painted the Scrovegni Chapel, but his fame and prosperity grew with every year, making him wealthy and well-known by the beginning of the fourteenth century. He had already spent decades painting religious frescoes throughout Italy and was much in demand by the public and clergy alike. Although di Bondone had several children at the time, he stayed in Padua for over two years to finish the chapel for the Enrico Scrovegni family of Padua.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Art Period

Giotto di Bondone painted the Scrovegni Chapel and many other works at the very end of the Medieval period. He was born in the time of the great Arnolfo di Cambio and his own critically neglected master, Cimabue.

Di Bondone's predecessors were solidly Byzantine; they painted in the traditional flowy, unrealistic and excessively holy style that had characterized European art for centuries. Di Bondone was the first artist to move away from this highly stylized way of painting and toward a more natural and realistic method.

In the Scrovegni Chapel, there is ample evidence of this. The facial expressions, gestures, and postures all communicate authentic human emotion, as do the colors used in each fresco. Di Bondone also used lines to focus attention on different areas of his paintings. For these unique and almost revolutionary methods, he is often called the father of the Renaissance.

Scrovegni Chapel Frescoes Bibliography

To learn more about Giotto and his artworks please choose from the following recommended sources.

• Derbes, A. & Sandona, M. The Cambridge Companion to Giotto. Cambridge University Press, 2004

• Eimerl, Sarel. The World of Giotto, C. 1267 - 1337. Little Brown & Company, 1967

• Norbert, Wolf. Giotto di Bondone. Taschen, 2000

• Richardson, Carol M. , et al. Renaissance Art Reconsidered: An Anthology of Primary Sources Wiley-Blackwell, 2006

• Paolettii, John T. & Radke, Gary M. Art in Renaissance Italy. Laurence King, 2005

• Nichols, Tom. Renaissance Art: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications, 2010

• Hartt, Frederick & Wilkins, David. History of Italian Renaissance Art. Pearson Education, 2010