Giotto di Bondone Style and Technique

- Full Name:

- Giotto di Bondone

- Short Name:

- Giotto

- Date of Birth:

- 1266

- Date of Death:

- 1337

- Focus:

- Paintings

- Mediums:

- Tempera, Wood

- Subjects:

- Figure, Landscapes, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Renaissance

- Hometown:

- Florence, Italy

- Giotto di Bondone Style and Technique Page's Content

- Introduction

- Style

- Method

Introduction

Giotto di Bondone is universally acknowledged as something of a pioneer in the art world, having taken the first artistic step toward the Renaissance. His career began in the time of the great Medieval artists, whose stylized Byzantine techniques he soon traded in for the earthly, natural style he is known for today.

Di Bondone looked to these artists and to his master, Cimabue, for cues on subject matter and location of his frescoes. Like his master and others, he decorated chapels, churches, altars and other religious locations, depicting beautifully intricate scenes from the life of Christ and the saints.

Though di Bondone had his start among the Medieval greats, he soon became a great in his own right, transforming the art world with his revolutionary painting style and technique.

Giotto di Bondone Style

While ultimately di Bondone chose to develop his own style of painting, as an apprentice he worked closely with his master, Cimabue. There is clear evidence that the two worked together on the ceiling of the Church of St. Francis in Assisi, portraying scenes from the saint's life.

However, even though this is considered di Bondone's earliest work, it is quite clear which of the scenes he was responsible for, his individual technique already beginning to clarify itself.

Di Bondone's style was wholly new and unique for its time. He moved decisively away from the flowing, unrealistic human figures in the Medieval works and gave rise to the movement of naturalism.

Naturalism, as it name suggests, is a practice of painting things exactly as they are; the emphasis is not on plainness or a lack of decoration, but on authenticity. Di Bondone placed great importance on the quality of "realness" in art and was the first artist to so closely observe humans and reproduce their gestures, expressions and movement in art. He continued this practice throughout his career, and it is evident from his earliest work to his last, in the Campanile of the Florence Cathedral.

Composition:

Di Bondone made excellent use of the space he was allotted, planning carefully both to maximize the all-important authenticity and to give his viewer a sense of involvement in the work. It is often said that, due to the way di Bondone arranged his subjects, the viewer often seems to have an actual place in the painting itself.

Di Bondone used horizon lines, diagonal lines (often in the form of heavenly beams) and other types of geography (i. e., mountains) to draw attention to the main idea of the fresco and to what he most wanted viewers to focus on.

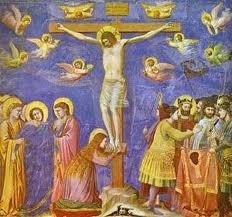

One particular example of this is in Lamentation of the Christ (Church of St. Francis, Assisi), where the downward-left diagonal line of the mountain in the background draws the eye to Mary holding her dead son, while John the Baptist throws his arms up and back in despair. The upward motion leads the eye to the sky above the lamenters, where angels are weeping for the death of Christ.

Color palette:

If di Bondone's compositional style could be called unique, his use of color could probably have been called almost blasphemous for his time. Dismissing the excessively-reverent, celestial tone of most existing religious works, di Bondone chose to substitute lovely natural blue skies for the typical "heavenly" gold ones so favored by Medievalists.

He gave authentic color to his subjects' clothing, hair and faces, eschewing the accepted standard of dull, nondescript details and all emphasis on the work's sanctity. He also incorporated bold greens, yellows, oranges and reds to communicate emotion, quite unusual at the time.

Where his predecessors had relied almost exclusively on gold and other "holy" colors, di Bondone's adherence to naturalism meant that he painted the world as it is - colorfully.

Use of light/shade:

Yet another way in which di Bondone broke the mold was to manipulate the effects of light and shade to communicate a sense of reality to the viewer. He used light and shade both to demonstrate the variety of settings earth (rather than the traditional, sacred-looking background) and to give life to his subjects.

In this way, di Bondone's lack of interest in Byzantine styles be seen: he did not paint his subjects as flowy and other-worldly, but as real people with weight and form that were governed by the laws of gravity. The use of light and shade draws attention to the realness of the human form by emphasizing curves, bulk, muscles, and other body lines. Di Bondone proved, in short, to be a master of chiaroscuro.

Mood, tone, & emotion:

Believing that to paint humans one had first to know what they really look like, di Bondone spent countless hours observing people in various states of emotion; fear, joy, shock, grief, anger, despair, and many other emotions all feature prominently in his work.

In The Stigmatization of St. Francis (Church of San Francesco, Pisa), di Bondone carefully manipulates the facial expressions of Jesus and St. Francis to communicate what both are feeling: St. Francis's face features a look of intense shock and awe as he falls to his knees and raises his arms in a deferential gesture of submission.

Jesus's expression is calm, knowing and peaceful as he grants the stigmata to a faithful servant. There are many such examples of di Bondone's use of mood, tone and emotion. In scenes of sorrow, he paints his subjects in an obvious state of abject grief, rather than the traditional, inclined-head look of regret.

Di Bondone may have sacrificed some of his subjects' dignity to truthfully portray their emotions, but in doing so he preserved their humanity for the centuries that would follow him.

Perspective:

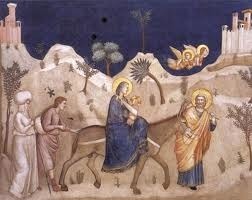

As previously mentioned, di Bondone painted his works so as to make his viewer feel like more than just a spectator; he wanted them to have a place in his scene. To that end, he often painted so that the viewer seems to be in the painting, observing at a discreet distance the action taking place.

This is particularly evident throughout the frescoes on the ceiling of the Scrovegni Chapel where, as di Bondone painted scenes from the lives of Mary and Jesus, he carefully arranged the figures so as to allow the viewer to feel as though he or she were, for example, walking along on the road to Egypt.

Brush stroke:

Di Bondone used very tight, thick brushstrokes, again in the interest of naturalism. He did not favor the weightless, flowing figures so popular in Medieval works, choosing instead to give weight and form to his subjects' flesh and clothing.

He painted both so as to make them appear to hang naturally from the body. Since he painted frescoes almost exclusively, his brush strokes are very thick and heavy, giving further weight to the subjects.

Giotto di Bondone Method

It can easily be said that Giotto di Bondone adhered for virtually his entire career to the same style, methods and techniques. His initial innovations, largely (if not totally) unaltered, spread throughout Italy and eventually Europe like wildfire, winning him lifelong fame and attracting any number of ardent followers and imitators.

Di Bondone's methods were ground-breaking at the time, and he spent most of his seventy years very slowly refining them. His earliest known work, at the Church of St. Francis in Assisi, does not noticeably differ from his final work at the Campanile in Florence.

Giotto's techniques - the non-stylized, bulky, emotional, authentic-looking way of painting humans, the bright and colorful scenery substituted for traditionally "holy" colors, and his dedication to naturalism - made him the definitive artist of his time.

His informal title of father of the Renaissance is not undeserved. Although the next step in the evolution of his style was not taken until Masaccio, di Bondone's style remains one of the most important contributions in the history of art.