Las Hilanderas

- Date of Creation:

- circa 1657

- Alternative Names:

- The Fable of Arachne, La Fábula de Aracné, The Spinners

- Height (cm):

- 220.00

- Length (cm):

- 289.00

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Madrid, Spain

- Displayed at:

- Museo Nacional del Prado

- Owner:

- Museo Nacional del Prado

- Las Hilanderas Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Inspirations for the Work

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

Las Hilanderas Story / Theme

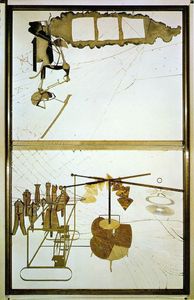

One of Velázquez's most ambiguous and complex masterpieces, Las Hilanderas (also known as The Spinners or The Fable of Arachne) is based on the story of the weaving competition between Arachne and the goddess Pallas Athena, from Ovid's Metamorphoses, book VI.

The tale holds that Pallas Athena, the patron goddess of weaving, challenged Arachne to a weaving competition when she heard the mortal woman bragging about her spinning skills. Athena executed a tapestry paying homage to the brilliant gods and goddesses of Olympus, with images of the painful tortures to which mortals are subject when they dare to defy their divine counterparts.

In anticipation of such a theme, Arachne wove a tapestry showing the Loves of the Gods, specifically The Rape of Europa, which showed Athena's own father indulging his all-too-human lust with a common mortal woman.

Enraged at the perceived insult, Athena threw a shuttle at Arachne's head and began subjecting her to abuse. Terrified and distraught, Arachne attempted to commit suicide by hanging herself. At the last minute, Athena took pity on the poor girl and transformed her into a spider dangling from the thread, doomed to weave forever.

The Commission:

As was often the case with Velázquez's paintings, the circumstances surrounding this commission are obscure. It is certain that Las Hilanderas was painted for a functionary of the Spanish court, Pedro de Arce, but little else is known about when or why it was commissioned.

Based on stylistic evidence (namely, the complexity of the composition and its lighter tonalities), art historians conjecture that the painting is a very late work, executed after Velázquez's second trip to Italy, most likely around 1657.

Las Hilanderas Inspirations for the Work

Although it isn't the most popular subject in the history of art, as a classical subject the myth of Athena and Arachne would have been a worthy one for any painter of the Renaissance or Baroque.

Furthermore, as a subject that centers on the creative act and the power of images, the myth could be a particularly interesting one for artists. The following interpretations were executed by artists with whom Velázquez was intimately acquainted and could have served as sources of inspiration.

Tintoretto, Athena and Arachne. c. 1585:

One of Velázquez's beloved Venetians, this master of the Italian Renaissance tried his hand at the Arachne myth near the end of the 16th century.

Tintoretto's soft, golden light and warm palette are utterly characteristic of Venetian painting, and the artist chooses an unusual vantage point, showing the two women weaving from below and giving the viewer an eyeful of Arachne's randomly exposed breasts, suggesting a potential underlying eroticism.

Rubens, Pallas and Arachne, 1637:

Rubens's interpretation of this theme was executed a few years after his trip to Madrid where he met Velázquez, around 1628-30. Rubens's sketch of a painting opts for the most dramatic moment of the myth, when Athena attacks Arachne in a fit of rage for her impertinence.

The image is imbued with the same golden, ochre tones of Tintoretto's painting, but whereas the artist chose a moment of quiet contemplation and concentration before the judgment takes place, Velazquez chose the most dynamic moment of violence.

Las Hilanderas Analysis

Composition:

In this mature masterpiece, Velázquez returns to a compositional device from his earliest bodegones.

A relative of the Italian pittura ridicola and Dutch genre scenes, the Spanish "bodegón" (derived from the Spanish word bodega, which can be translated as pantry, tavern, or wine cellar) is another type of genre scene that shows common people with food, often with an implicit moralizing message.

Velázquez was a pioneer of this genre, and his early works (from 1618-1620) are almost all bodegones. Compared to Italian or Dutch examples of similar themes, these paintings are relatively sober, restrained and dignified, lacking any overt mockery or buffoonish humor.

Velázquez's bodegones are characterized by:

• Sobre, limited palette of earth tones (reds, browns, black)

• Shallow pictorial space (typical of Spanish painting)

• Careful attention to still-life elements

• Dignified portrayal of the human subject

• Serious tone

Just like in works such as The Supper in Emmaus, Velázquez divides his composition into two distinctly separate realms, a separation made clear both by space, the elevation of the background scene, and differences in light and brushstroke.

Color palette:

Las Hilanderas is lighter in tone and brighter in palette than most of Velázquez's earlier works, which most likely speaks to the influence of the artist's second trip to Italy. This being said, the painting still evidences the interest in chiaroscuro so typical of Velázquez's style, and is dominated by one of his favorite triadic palettes, red, blue and brown.

Tone:

The various interpretations of Las Hilanderas (see Critical Reception) mean that there are different tones that can be detected in this painting. One art historian has suggested that Las Hilanderas could have erotic undertones and in contemporary Spanish culture, spinning was a popular sexual metaphor.

Bird makes a case for this painting as referring to this popular imagery for a number of reasons. The lower-class women in the foreground are shown in an intimate, unguarded moment, provocatively revealing what most Spanish women took great pains to hide: ankles, arms and necks.

Furthermore, certain symbols in the painting were common symbols of "luxuria," or lust, during the Renaissance and Baroque periods: the cat, a fickle creature, symbol of femininity and prostitution; the bobbin that one spinner holds in her lap, a symbol of female genitals; and the viola da gamba propped up in the background, a common metaphor for sexual relationships between men and women.

In this context, the separation of the women in the foreground and background would take on another meaning. The earthly, laboring figures in the foreground represent sensuality and physical appetites, while the modestly clothed maidens in the background, protected by Pallas Athena, the goddess and protector of virgins, represent a higher spirituality.

Las Hilanderas Critical Reception

Perhaps even more than Las Meninas, Las Hilanderas is one of the most complex and obscure of Velázquez's paintings. One art historian has eloquently argued that as part of his attempt to prove that painting was a liberal art, Velázquez intentionally imbued his works with erudite, complex, multiple layers of meaning, even leaving false trails and red herrings to test his viewer's learning and understanding to the utmost.

Thus, although the interpretation of Las Meninas has been more or less widely accepted, the ultimate meaning of Las Hilanderas remains obscure, and each new generation of art historians proposes new interpretations, many of which could be concurrently valid.

The first and most commonly accepted interpretation of Velázquez's Las Hilanderas was that the painting is a genre scene representing contemporary women working in the Santa Isabel tapestry shop.

In 1948, art historian Diego Angula produced a convincing argument that the iconography of Las Hilanderas suggests the Fable of Arachne. This interpretation followed the identification of the helmeted figure in the background as the Pallas Athena, and the tapestry visible to the viewer as the Rape of Europa, the subject that Arachne was said to depict.

In fact, the tapestry has even been identified as a copy after Titian's Rape of Europa, which was one of the most prized items in the Spanish royal collection. The Titian painting was copied by Rubens in 1629, a copy which constituted another prize item in the royal collection.

The reference to Titian and Rubens's copy of the Italian master may suggest another reading of the painting. Some art historians have suggested that the painting refers to the passage of time, and how the work of the old masters will be replaced by the masterpieces of the new generation.

One of the most common interpretations of Las Hilanderas is that it is a picture about art et usus, or art versus craft, another point in Velázquez's argument for painting as being a liberal art, distinct from the plebian, lowly world of craft and manual labor.

The spinners in the foreground, submerged in the shadows of ignorance, represent base craft, whereas the tapestries in the elevated background, graced with the light of divinity and knowledge, represent the elevated world of art.

What is truly amazing about Velázquez's Las Hilanderas is the fact that not only can so many interpretations exist, none of them are mutually exclusive. All of these interpretations could hold true at one and the same time. This is surely the sign of a true masterpiece.

Las Hilanderas Related Paintings

Las Hilanderas Artist

When Velázquez first entered court, the established painters scoffed at the unproven young talent, calling him only good for mediocre portraits and lacking the scope for subjects of greater weight. Velázquez proved the naysayers wrong, works like Las Hilanderas, which is among the most exquisite in the history of art.

Velázquez has not ceased to be a remarkably fecund source of inspiration for art critics and art historians up until the present day, nor has his reputation as one of the greatest painters of all time been dimmed.

Velázquez paved the way for early nineteenth century realist and impressionist painters, especially Édouard Manet. Since then, he has gone on to influence artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, and Anglo-Irish painter Francis Bacon. Such artists have demonstrated their love for the works of Velázquez by recreating some of his most noted paintings.

Diego Velázquez was hailed a father of the Spanish school of art and is one of the greatest artists that ever lived.

Las Hilanderas Art Period

Diego RodrÍguez de Silva y Velázquez was born into a society of paradox: Spain was simultaneously undergoing one of the most dramatic economic and political declines of any nation in European history, and unprecedentedly fertile, creative bursts of artistic activity.

In Velázquez's hometown of Seville in particular, circles of Humanist learning, arts and letters and philosophy all flourished, constituting a particularly fecund environment for a young artist.

On the other hand, Velázquez's chosen profession would become a significant obstacle in the artist's personal agenda. Spanish society was obsessed with nobility, and unlike in Italy, the visual arts were emphatically not equated with noble pursuits like literature or philosophy.

Artists were seen as essentially vulgar craftsman who worked for a living with their hands, just like blacksmiths or tailors. Making matters even more complicated, the Catholic church exercised almost total power over the arts in Spain, dictating everything from subject to composition, meaning that artists had very little room to experiment or grow. Velázquez was thus fated to struggle from the very incipience of his career.

While most artists of the Baroque period suffered from a serious drop in critical opinion during the 18th century, eventually fading into oblivion until being rediscovered in the 1950s, Velázquez took an alternate route.

Because of Spain's political situation, the nation was more or less isolated from the rest of Europe during the heights of Neoclassicism, meaning that Velázquez's reputation was safe from the hands of Baroque-haters like Wincklemann, who managed to destroy the reputation of such artists as Caravaggio, Carracci and Bernini.

By the time Spain opened up to the rest of Europe in the beginning of the 19th century, the world was ready for Velázquez, and critics and artists alike haven't ceased singing the master painter's praises.

Las Hilanderas Bibliography

The following list offers some of the best sources of further reading on Velázquez and his works.

• Brown, Dale. The World of Velázquez: 1599-1660. Time-Life Books, 1969

• Brown, Jonathan. Velázquez, Painter and Courtier. Yale University Press, 1986

• Carr, Dawson, et al. Velázquez. Yale University Press, 2006

• Davies, David, et al. Velázquez in Seville. National Galleries of Scotland, 1996

• Harris, Enriqueta. Velázquez. Phaidon, 1982

• Kahr, Madlyn Millner. Velázquez: the art of painting. Harper and Row, 1976

• López-Rey, José. Velázquez: A catalogue raisonné of his œuvre. Faber and Faber, 1963

• Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso, et al. Velázquez. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989

• Wolf, Norbert. Diego Velázquez, 1599-1660: the face of Spain. Taschen, 1998

• Wind, Barry. Velázquez's Bodegones: A study in 17th century Spanish genre painting. Fairfax: George Mason University Press, 1987