The Fortune Teller

- Date of Creation:

- 1598

- Height (cm):

- 99.00

- Length (cm):

- 131.00

- Medium:

- Oil

- Support:

- Canvas

- Subject:

- Figure

- Art Movement:

- Baroque

- Created by:

- Current Location:

- Paris, France

- Displayed at:

- Musée du Louvre

- Owner:

- Musée du Louvre

- The Fortune Teller Page's Content

- Story / Theme

- Analysis

- Critical Reception

- Related Paintings

- Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

- Artist

- Art Period

- Bibliography

The Fortune Teller Story / Theme

With The Fortune Teller, Caravaggio introduced a new subject into Italian art. Unlike most Italian paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, The Fortune Teller does not take its theme from the Bible or Greco-Roman mythology, but instead is a genre picture, or a scene of daily life.

Genre paintings were extremely popular in Northern Europe, abounding in Dutch art. Northern paintings and prints were becoming quite popular at the end of the sixteenth century especially in northern Italy and Caravaggio most likely became familiar with them during his years as an artist's apprentice in the Lombardy region.

Caravaggio depicts a wealthy, foppish young man having his palm read by a seemingly innocent gypsy girl (identifiable by her unique attire). Naively trusting and apparently easily distracted by the fairer sex, the boy flirtatiously gazes into the gypsy girl's eyes while she (according to contemporary sources) slightly slips the ring off his finger. Just like Northern genre paintings, the painting is imbued with a subtle moral lesson.

Contemporary sources say that Caravaggio even went so far as to invite a gypsy girl from the street into his studio to pose as his model, a practice unheard of at that time. The artist was famous for preferring to work from nature and drawing inspiration from every day events to studying the masters.

The Louvre version of The Fortune Teller is Caravaggio's second on this theme and the dates of both works are disputed. The first was painted for the open market, and sold for only 8 scudi. The work was acquired by the wealthy banker Marchese Vincenti Giustiniani.

Cardinal del Monte, Caravaggio's first important patron, was so admiring of Giustiniani's painting that around 1595 he commissioned another version from Caravaggio for himself, which is the version currently in the Louvre.

The Fortune Teller hangs in the Louvre today because it was acquired in the 17th century for Louis XIV. When it arrived to its new home, in order to make the painting match the size a neighboring artwork a strip of canvas was added to the top, and the feather on the boy's hat was embellished. Today, a careful observer can see the line where the strip was added on.

The Fortune Teller Analysis

Caravaggio's unprecedentedly faithful realism and his careful attention to detail are already present early works such as The Fortune Teller.

Composition:

Several characteristics unique to Caravaggio's early style are evident, in terms of realism and attention to detail. Caravaggio's early paintings always take place indoors, with the figures placed in front of an empty, ambiguously defined neutral background.

Furthermore, every aspect of this painting was carefully studied from life. Even the young man's sword is clearly identifiable and the gypsy girl's dress corresponds exactly with contemporary descriptions: "as only dress an old blanket, very coarse and fastened on the shoulder by a band of cloth or cord, and underneath a poor shift for all covering."

There is a feeling of conspired serenity in this work due to the fact that compositional symmetry is created with each model occupying roughly half of the canvas. The two figures produce a round arch, with the young man's head-dress marking the pinnacle.

A careful study of Caravaggio's paintings reveals that he often used the same model and even later in life would continue to paint these early models' features from memory. Here, the boy's face has tentatively been identified as that of Mario Minniti, a Sicilian painter who was Caravaggio's roommate before the more famous artist entered the court of Cardinal del Monte.

Use of light:

Light almost always enters from the upper left hand corner of the picture plane in the artist's early paintings.

Color palette:

The color palette used for this peace also creates a feeling of serenity. Warm golden-brown tones of the skin and the background are blended with soft lighting, and set off by the whites, greens, reds and browns of the garments and this adds to the painting's symmetry.

The Fortune Teller Critical Reception

Bellori, Caravaggio's biographer states that the artist hand-picked the gypsy girl on the street to prove that he did not need to copy the works of the masters from antiquity: "(W)hen he was shown the most famous statues of Phidias and Glykon in order that he might use them as models, his only answer was to point towards a crowd of people saying that nature had given him an abundance of masters. "

It was a well-known fact that Mannerists artists of Caravaggio's day who were classically-trained did not approve of his preference for painting from life instead of from copies and drawings made from older masterpieces.

Bellori adds, "... and in these two half-figures [Caravaggio] translated reality so purely that it came to confirm what he said. "

Today this story is mostly believed to be untrue as Bellori was writing more than half a century after Caravaggio's death, and neither Mancini nor Giovanni Baglione, the two contemporary sources who had known the artist mention it. Nevertheless it does show the impact Caravaggio had on his contemporaries and also his disproval of the Renaissance theory that art was a didactic fiction and instead that it could represent real life.

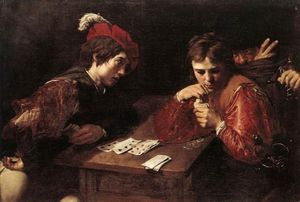

The Fortune Teller Related Paintings

The Fortune Teller Locations Through Time - Notable Sales

According to Mancini, Caravaggio was so poor that he was forced him to sell The Fortune Teller for just eight scudi. It entered the collection of the Marchese Vincente Giustiniani, a wealthy banker and connoisseur who became a major patron of Caravaggio. Giustiniani's friend, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, purchased the companion piece, The Cardsharps, in 1595.

The Fortune Teller Artist

Caravaggio's paintings constitute some of the most stunning works in the entire history of Western art and played a key role in defining 17th century Italian art.

Caravaggio initiated tenebrism in Italy. He was a rebellious spirit and a life observer who wanted to remain true to reality in his works. His paintings evoked emotion and this style was not well received as society was not ready for this revolution.

He bathed his subjects in light to add a plasticity to his figures while everything else was painted in shadows and semi-darkness. This process has been called "cellar light" and was hugely influential among baroque painting.

Caravaggio was as controversial for his revolutionary artworks as he was for his infamous temper and lengthy police record. He ignored the rules that artists from the previous century had followed and instead developed a love of realism and his emotional directness was unrivalled.

In the 20th century when emerging artists were adopting his techniques and imitating his style. Caravaggism had profound effects on the art world and artists that were directly and indirectly influenced by Caravaggio include Rubens, Hals, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Velazquez and Bernini.

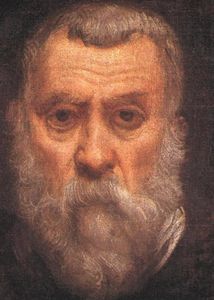

The Fortune Teller Art Period

The Baroque style originated in Italy and its pioneers include great artists such as Michelangelo and Tintoretto. Baroque art focused on impersonal and generic works with an animated and energetic mood. The success of this art genre was promoted by the Roman Catholic Church and the aristocracy, the latter of which saw Baroque art as a means of demonstrating wealth and power.

Caravaggio is a pioneer of the Italian Baroque style that grew out of the ruins of Mannerism. At the end of the 16th century, the artist was exposed both to the artistic reforms of the Counter-Reformation as well as to a new interest in scientific naturalism flourishing in northern Italy, due in part to the influx of artworks from northern Europe. Out of this context, Caravaggio developed a style of unflinching realism, unprecedented approachability and a direct appeal to the emotions that had no equal among his peers and helped to mould 17th century Italian art.

Italian Baroque art was not widely different to Italian Renaissance painting but the color palette was richer and darker and the theme of religion was more popular. There remains some mystery surrounding the true derivation of Italian Baroque but some argue that the word 'Baroque' comes from the Italian "Barocco".

Caravaggio's influence is evident both directly or indirectly in the paintings artist such as of Rubens, Bernini, Jusepe de Ribera and Rembrandt, and the next generation of artists profoundly influence by Caravaggio were labeled the "Caravaggisti" or "Caravagesques", as well as Tenebrists or "Tenebrosi" ("shadowists").

Bernard Berenson agreed: "With the exception of Michelangelo, no other Italian painter exercised so great an influence".

The Fortune Teller Bibliography

To read more about Caravaggio and his works please refer to the recommended reading list below.

• Bernedetti, Sergio. Caravaggio: The master revealed. Dublin: The National Gallery of Ireland, 1993

• Freedberg, S. J. Circa 1600:A revolution in the style of Italian painting. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press, 1983

• Friedlander, Walter. Caravaggio Studies. New York: Schocken Books, 1969

• Gilbert, Creighton. Caravaggio: his two Cardinals. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995

• Hibbard, Howard. Caravaggio. New York: Harper and Row, 1983

• Hinks, R. P. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio: His life, his legend, his works. London: Faber & Faber, 1953

• Langdon, Helen. Caravaggio: A life. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1999

• Mancini, Giulio, Giovanni Baglione, and Giovanni Bellori. Lives of Caravaggio. London: Pallas Athene, 2005

• Moir, Alfred. Caravaggio. New York: H. N. Abrams, 1989

• Varriano, John. Caravaggio: the art of realism. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006